-

-

Calzolari’s first exhibition at Marianne Boesky Gallery in 2012 was the artist’s first in the United States in more than twenty years. His 2022 solo show with the gallery was the first exhibition of his work in the United States in five years. In 2019, Calzolari was the subject of a major retrospective, Painting as a Butterfly, at the Madre Museum in Naples, Italy, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva and Andrea Villani. Calzolari’s work is included in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; Sammlung Goetz, Munich, Germany; Centre Pompidou, Paris, France; and Palazzo Grassi, Punta della Dogana François Pinault Foundation, Venice, Italy, among others. He has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Documenta IX, Kassel Germany; Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris, France, Venice Biennale, Italy; Ca’ Pesaro, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Venice, Italy; the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. The artist currently lives and works in Lisbon, Portugal.

-

-

-

-

-

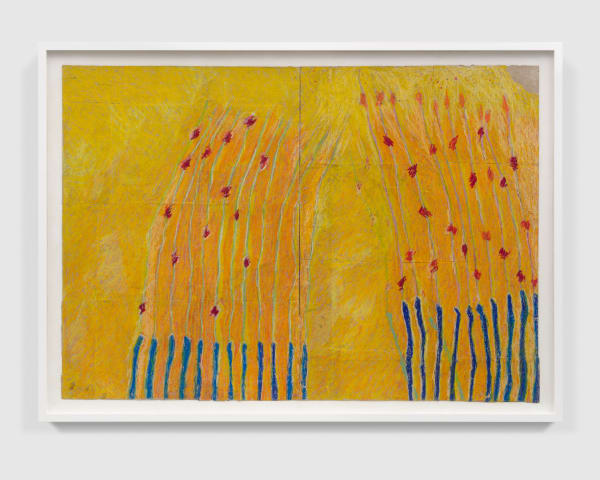

Untitled, 2010

-

-

-

-

-

Calzolari, Pier Paolo | Artist Overview

Current viewing_room

![Haïku [Scarpetta rosa], 2017](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/boeskygallery/images/view/e28e5499f70c5afa4833b152f046e88aj/marianneboeskygallery-pier-paolo-calzolari-ha-ku-scarpetta-rosa-2017.jpg)

![Haïku [scarpetta grigia], 2017](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/boeskygallery/images/view/576d4911ed71d02bb790b597bb8a700fj/marianneboeskygallery-pier-paolo-calzolari-ha-ku-scarpetta-grigia-2017.jpg)

![Untitled [KOSAME], 2021](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/boeskygallery/images/view/8a741681bc31a81f5065c310f8dc7de7j/marianneboeskygallery-pier-paolo-calzolari-untitled-kosame-2021.jpg)