BY CLAYTON PRESS

After World War II there was a short-lived micro-explosion of national character studies by anthropologists and sociologists. These efforts sought to establish and explain modal personalities, that is, the traits or characteristics typical of the society in which a person lives. Put another way, these studies tried to capture national psyches.

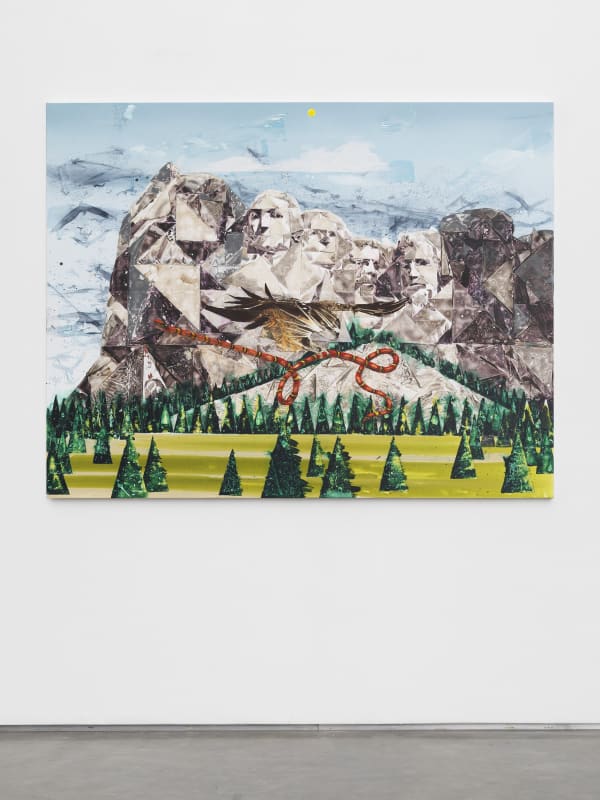

Barnaby Furnas: Frontier Ballads is a focused, incisive study of the American psyche, which is neither uniform nor cohesive. Furnas is a history painter. He reaches back to pioneering America with familiar images: from wranglers swinging lassos to the Mount Rushmore National Monument. He interprets the present using Grant Wood-like farm chorines and modern day political rallies. He mixes and matches the free-spirited cowboy with the modern political Svengali, resulting in a picture of a fractured American spirit.

The surface of his paintings can be disorienting. They offer a near-cinematic experience (with an easily imagined soundtrack). His paintings are like freeze frames, action arrested allowing for closer scrutiny. Nonetheless, his canvases are alive with activity and create an inaudible sense of sound. Furnas himself has said, “Paintings don’t show one minute happening. They can show an hour of things happenings.” Consider:

- The Rally. A blue-suited, red-tied man—most likely Donald Trump—is the central figure. The painting captures a crowd of raised hands “saluting” the “politician,” who is waving a stiff arm to the throng. Jets are flying overhead. They crisscross the sky in an aerial flyover or a preemptive strike. You can almost hear the turbines scream.

- The Wrangler. A cowboy rides a burly bison, his bandana trailing streaks of orange (a recurring motif in this body of work), his lasso—an open noose—motionless overhead. The lasso casts a ghostly shadow of speed and circulation. Streaky clouds are overhead, inhabited by a flock of birds.

- Untitled Remains. Ravens and raptors pick at a corpse, explosive blood splatters and torn arteries and veins decorate the canvas’s surface. (One raven has plucked a tasty eyeball.) Beneath the fallen military-uniformed corpse lies another one, mirrored in reverse, underground in a more advanced stage of rot.

All of Furnas’s paintings have a quality reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic motion studies. Like Muybridge, he blends art and technology to stop time while simultaneously suggesting movement. Furnas’s own experiments with technology let him build surfaces that convey tactility. He betrays the traditional flat canvas with an array of techniques: pouring, splashing, patterning and burning. It is rough stuff, sometimes suggesting a physical assault on the canvas. The effects are compelling.

Furnas uses a full palette, creating almost liquid, living surfaces. The works are eye popping. Throughout his career Furnas has used water dispersed pigments, dyes, acrylics—really almost every manner of “paint” media and technical choices—to activate his work, which Peter Eleey, Chief Curator at MoMA PS1, has described as “tightly controlled and delicately balanced, though, hovering between order and chaos.”

So accomplished is Furnas that his paintings almost seem to emit sound. It is as if you can hear the roar of jets overhead, the thunder of the bison’s hooves and the rasps and screams of the birds of prey. This is an impressive, unique achievement to stimulate the notion of sound in painting without resorting to gimmicks or appliances. You can almost hear the vocal harmonic chord of heaven’s angelic choir in The Trio (Grand Ole Opry) and The Quartet.

Historical painting, even narrative painting, has had more downs than ups in contemporary art. There is resistance to the traditions that emerged in the European art academies between the 17th and later 19th centuries, where universal, timeless truths were taught. In fact, history painting was more specifically aimed at public education rather than private enjoyment.

Most narrative and historical paintings are static, time capsules. Look back in art history at Nicolas Poussin’s The Dance of the Music of Time (1634-1636) or Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul, crossing the Alps at Great St Bernard Pass (1801-1805). History is arrested, is preserved. Time will not resume. These are spare compositions meant to teach, uplift and inspire.

In terms of contemporary history painting, we can look to artists like Roger Brown, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero and Mark Tansey for comparisons. (A focused exhibition of Leon Golub’s work is currently on view at The Met Breuer.) Golub and Spero were committed political activists and faithful to historical painting's didactic intentions. Brown and Tansey differ in their less literal approach to storytelling. They also best share Furnas’s ability to freeze-frame events. But the differences in content, style and technique are significant. Brown’s story paintings are rendered in strong, even lurid colors in an almost woodcut print style. Tansey’s allegories are almost photographic monochromes.

This exhibition tackles American heritage and, certainly, MAGA-ism. History is recorded, but time seems ready to be resumed, advanced. Furnas, the spirit catcher, has captured some key elements of the American psyche. He digs deep, looking for national character and spiritual core. He asks, “What moral truths await us?”