BY KATIE WHITE

Brazilian artist Thalita Hamaoui only knew Romania through her grandmother’s vivid, colorful tales that played out in her imagination.

“She had so many stories and they were all in my head,” said the artist during a recent conversation. Hamaoui, who was born in 1981 and raised in Saõ Paulo, is the daughter of a Romanian mother and Egyptian father. She had never seen the forests and houses, smells, and sounds her grandmother described.

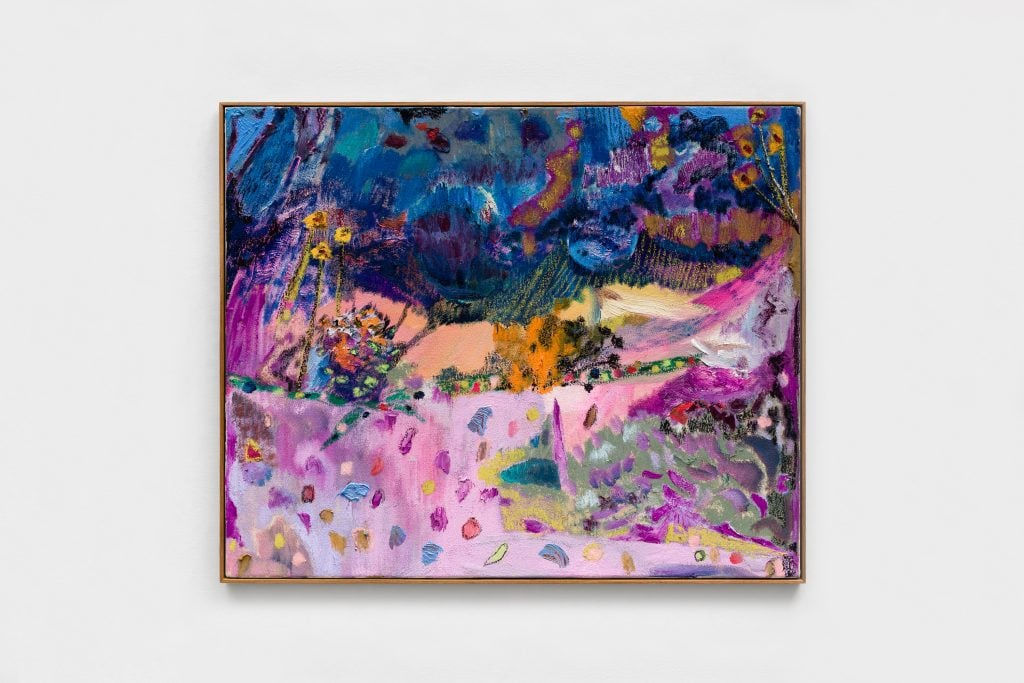

Thalita Hamaoui, Nascer da terra (2025).

Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery.

Recently, Hamaoui tasked herself with painting the lands she had imagined when she heard her these passed-down family tales. “I had recently lost my grandmother,” she said, “I decided I wanted to paint these stories.” The results are large-scale, kaleidoscopic, jewel-toned landscapes that embrace the folkloric and the fantastical. These works make up “Nascer de Terra,” her New York debut now on view with Marianne Boesky (through June 14).

“It’s like literature. When you read something, you create an imaginary world,” the artist explained, “We can read the same text and create different worlds in our minds.”

Hamaoui’s visions are a feast for the eyes, richly saturated with color and filled with dreamlike terrains that coalesce through the rhythmic layering of forms. These landscapes, marked by hillsides and seas, are absent of human and animal life, but are rife with plants, which bloom explosively, magically, filling the skies like pops of fireworks.

“I thought I was going to be painting the house my grandmother grew up in. Then I spent half an hour painting the house and 10 days painting the landscapes outside, when I realized this is about the land in my grandmother’s stories,” recalled the artist.

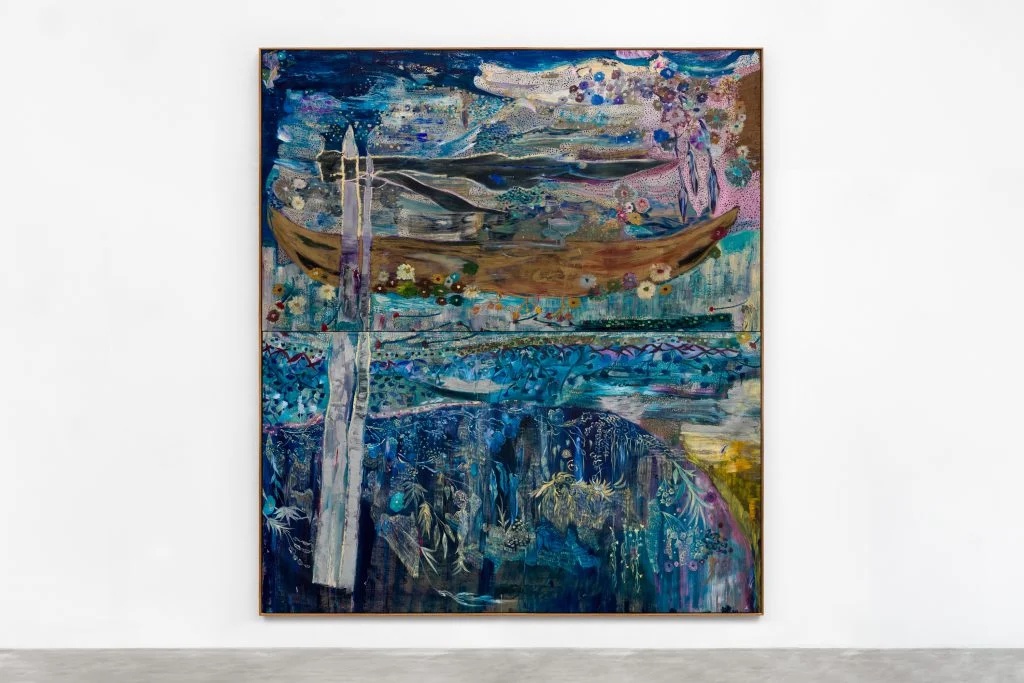

Thalita Hamaoui, Zana (2025).

Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery.

The terrains—the trees and the flowers—seem more akin to tropical Brazil than what one would equate to Romania, however. Hamaoui, who studied Fine Art at the Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado and has shown with Simões de Assis, in Curitiba, Brazil, is known for her resplendently colorful landscapes that document her native surroundings.

“I’ve never been to Romania. I was born and raised in Brazil and only know the chaos of the tropical environment. I couldn’t get far from what I knew,” she said. When my grandmother told me about running through a red forest, it became a tropical landscape in my mind.” In the exhibition, the red forest appears in the monumental canvas Nascer da terra (2025) in the form of brilliant red and magenta sloping hills under rainbows.

Hamaoui works on many paintings at a time, popping in and out of her compositions in bursts of recognition and resolution. She doesn’t draw in preparation for her paintings, instead preferring to work out her composition instinctually. She does draw, however, and the exhibition includes a selection of drawings made in oil pastel, chalk, and tempera on linen. She began these compositions during the lockdown, when, without access to art supplies, she and her son began drawing on a set of dark linen curtains she had bought for her house. The largest drawing in the show, A noite, a travessia, a memória, is a triptych divided into three shaped canvases that vaguely resemble a craggy mountain peak. At once, these forms could appear like bent or turning figures. The flattened forms in these works hint at Hamaoui’s burgeoning interest in Eastern art, where she suggests depth through a layering of forms.

Thalita Hamaoui, A noite, a travessia, a memória (2025).

Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery.

Her influences are myriad, however. She mentions the artists of the Brazilian Tropicália movement of the late 1960s who celebrated the colors, rhythms, and landscapes of Brazil, rather than aspiring toward European standards. Alberto da Veiga Guignard, a 20th-century Brazilian painter known for his whimsical bird’s eye landscapes of the state of Minas Gerais, is also an artist she returns to. Hamaoui confesses that she “loves the Post-Impressionists,” too. She is especially drawn to Bonnard, with his almost psychedelic layering of marks.

The exhibition includes a series of more intimately scaled compositions—a challenge for an artist who loves to work in bold, bursting gestures in her massive Saõ Paulo studio. In these works, such as Zana, (2025), the compressed dynamism of mark-making strategies is reminiscent of Bonnard. Her fantastical floating flowers, however, recall something of Odilon Redon, or even, at moments, the weightless wonderment of Marc Chagall.

Seen from a distance, or in photographs, Hamaoui’s compositions can resemble textiles, perhaps weaving or embroidery. After graduating from art school, she worked for many years in textile printing, learning the strength of forms and colors. About a decade ago, Hamaoui returned to painting, first working in watercolor and gouache, and then embracing oil.

Thalita Hamaoui, A linha que separava o céu da terra (2025).

Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery.

There are remnants of that textile sensibility, however, in her grasp of graphic form and color and also with the expressive freedom she brings to her representational forms. The luminous colors she favors bring to mind folk art textiles, including those found in Romania. She also paints on linen, in a range of tones that affect her approach to a composition. “I don’t like painting on white. I need something with more drama,” she laughed, “I like drama.”

Across the exhibition, one begins to notice a repetition of forms echoing throughout the works—thin moon-like canoes, consecutive rainbows, rising orbs of the moon or sun, trees reaching and bending, that give these works a shared architecture around us, even if each image is its own world. “It has to be colorful,” she said. “That’s Brazilian, and I can’t run away from that. It’s in me. All I heard in university was that being an artist in Brazil, being a painter, being a woman, being a mother, is a revolutionary decision. In this landscape, you can be settled, but you can be strong.”

Thalita Hamaoui, Constelação pensamento (2025).

Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery.