BY KATYA KAZAKINA

In partnership with the Association of Women in the Arts, Artnet presents a series of stories amplifying the voices of women shaping the fine-arts sector. Through candid conversations, industry leaders and emerging talents share their experiences, challenges, and visions for the future. These stories, paired with insights from our groundbreaking survey on gender equity among arts professionals, offer a deeper understanding of the barriers women face—and the transformative change they are driving in the art world.

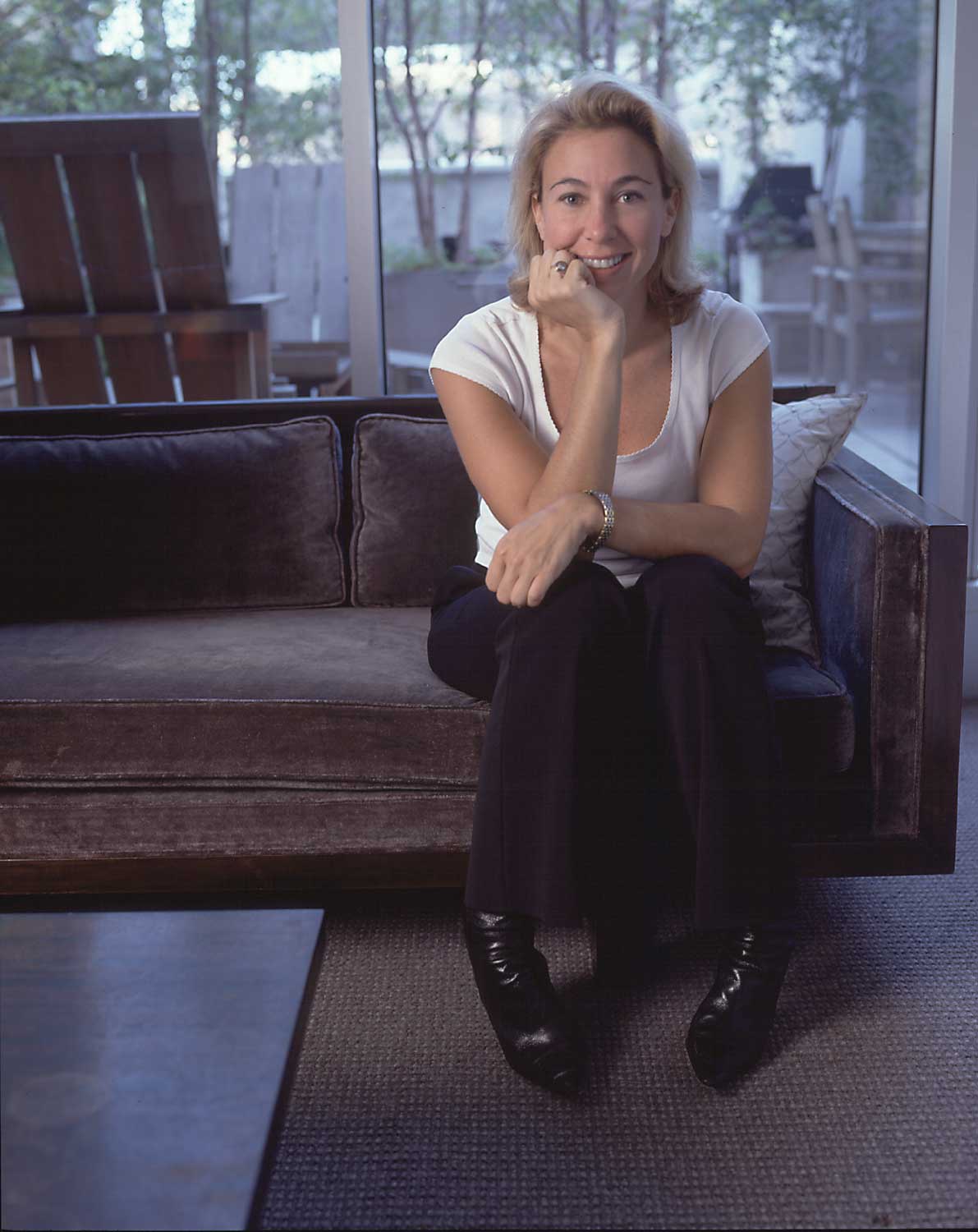

One of the leading female gallery owners in New York, Marianne Boesky, 58, is what many may call a powerhouse. Since founding her gallery in 1996, she has played a pivotal role in shaping contemporary art, launching the careers of major artists such as Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara, and Lisa Yuskavage. While some of her early discoveries were later poached by larger galleries, Boesky persevered, evolving her program and championing a new generation of talent.

Today, her gallery represents 29 artists and estates, over half of them women, including rising stars Michaela Yearwood-Dan and Danielle Mckinney. She also hasn’t let the competition beat her—in fact, they’ve joined her. In 2012, Boesky collaborated with the mega gallery Pace, which lured away Nara from her stable, to stage an unforgettably ambitious exhibition of Arte Povera artist Pier Paolo Calzolari. In 2014, she also joined forces with fellow dealer Dominique Levy to co-represent Frank Stella during his final decade.

A trailblazer, Boesky was early among blue-chip galleries to represent Black artists like Sanford Biggers, and she opened a pop-up in Aspen before pop-ups became an industry trend. (She now has a permanent outpost in Aspen, in addition to two spaces in Manhattan.) Boesky spoke to me about the evolving art market, how she navigated the challenges of motherhood while growing an internationally renowned gallery, and what it takes to thrive as a woman in the industry.

When you opened the gallery in 1996, was the art world a friendly place for women? Did you have any mentors and if so, who and what form did that take?

When I opened the gallery, I was 28 years old and believed anything was possible if you just worked hard enough; that women were only as oppressed as they let themselves be. I can’t say I had any concrete plan. My goal was clear though—to be able to make enough money to pay my bills and live an interesting life among artists. I would say artist Lisa Yuskavage was the most instrumental woman in my trajectory at this time. She challenged me to take my first space on Greene Street and to pursue excellence in every facet of becoming a gallerist.

As a woman, I did experience the reality of certain structural resistance. For example, when I first went to secure a line of credit with a bank before signing the lease for my first gallery space, I was asked by the banks for a co-signor they could rely on to be the “responsible party.” Subtle but not so subtle. But the incredible women gallerists in Soho at the time—such as Paula Cooper, Andrea Rosen, Barabara Gladstone, and Helene Wiener and Jenelle Porter of Metro Pictures—were running their own galleries with such success and confidence, that I believed if I kept my head down and worked hard for my artists, it would all work out. I think my naïveté ultimately served me well.

How has your vision for the gallery evolved over the years, especially after becoming a mother and later a single mother? Given the demands of constant travel, late-night events, and Saturday openings, running a gallery is an all-consuming job—how have you navigated these challenges as a parent?

Becoming a mother in 2004 was the greatest thing in my life and led to the most stressful period in my career. I traveled relentlessly all over the world, often taking my daughter and a nanny, to not compromise my work for and with my artists, but the energy directed back at me was punishing at times. It seemed certain men, and surprisingly certain women as well, just did not think having a child could or should coincide with also having a successful career. The schadenfreude was palpable at times. I lost artists. But I kept going.

Did you manage to maintain a work-life balance? Were there moments when you felt overwhelmed or pushed to your limits? How did you navigate those challenges and keep things running?

I was stretched, but my work was (and is) my life and my joy. And my daughter was an incredible trooper, coming with me everywhere for the first five years of her life. When she started school, she consoled me before trips because she knew I would miss her so much. I kept my travel to a five-day rule—I was never gone more than five days. And I never missed important dates like birthdays or school performances. I recall one May trip to Hong Kong that had me on the ground there for 48 hours so I could make the art fair opening day and still make it home in time for a my daughter’s birthday. It was exhausting but there was also a sense of exhilaration that my body could do it, and my mind felt proud for getting it done.

You have reinvented your gallery several times. Some of these changes, like your big expansions, coincided with dramatic moments in your personal and/or professional life. I remember when you built the space on West 25th Street for Takashi Murakami, only for him to leave the gallery soon after. Can you talk about some of these moments and what you learned from them as a businesswoman in the art market?

By 2004, several of the gallery’s artists had hit “star” status. Yoshitomo Nara, Sarah Sze, Yuskavage, Murakami. I wanted to grow with them. Gallery poaching was not yet a norm in our business, so I grew less out of fear of losing artists than of desire to meet them where they were and give them a bigger platform. In hindsight, it is not lost on me that two artists decided to leave the gallery within two years of me becoming a mother. It was stressful and I was young enough that it felt really personal. I had to make some difficult business decisions to stay afloat to complete the new building construction and once built, I was faced with a beautiful new space that felt outsized for the gallery without some of these artists to fill it. Being a gallerist involves having close relationships with artists. What I learned from this time was how to get back up and not take things so personally.

You have collaborated with Dominique Levy on representing artist Frank Stella. Were there similar collaborations with male colleagues? How were the experiences different?

My collaboration with Dominique was unusual because our galleries are in the same city. We both understood how complementary our contributions could be for Frank and we were incredibly successful together. I love collaborating with partner galleries. It can be fraught, but it really doesn’t have to be. I have collaborated with both men and women gallerists and have only had a few instances where it didn’t work, each for a different reason. But that’s pretty good odds for 29 years of collaborating with other dealers.

Hardwiring Change, a recent survey by Artnet and the Association for Women in the Arts (AWITA), found that there’s is strong desire for mentorship among women at all career levels within the art trade. Are you involved in anything like this, either through organizations, group events or personal one-on-one relationships within your gallery our outside of it?

As the art world has expanded into a full-blown industry, this does not surprise me. I have participated in talks at Columbia University and Sotheby’s Institute and always do my best respond to students and younger colleagues when they reach out. Being a primary gallerist can be isolating in the art world because it is such a competitive business.

You represent 15 female artists out of 29, and at least half of your staff are women. Was this intentional? How does this compare to your gallery’s early years? When did this shift happen, and what influenced the change?

I wish I could say the diversity in our program and staff was conscious or a result of conscientiousness up until 2020. I really just pursued artists I found interesting and exciting, whether emerging or mid-career and under-recognized. After George Floyd’s murder in 2020, which sparked a wave of protests against racism and police brutality, I felt the reckoning in this country and also realized I had to un-learn the idea that having been raised to be “color blind” was nothing to be proud of. Color and gender matter and I am more conscious, intentional, and more proactive now.

From your perch, what are the biggest challenges facing women’s advancement in the art world?

The biggest challenges that remain are the deeply entrenched views about the role women are meant to play. Gallerists must nurture their artists’ talents, but women gallerists doing their jobs well should not be confused with being motherly. Somehow that description is meant to degrade a female gallerist, which makes it more insulting! Women can be great business leaders and also great mothers. These are reinforcing roles and they can be truly complementary—and not at all mutually exclusive.