MICHELLE LANIER AND ALLISON JANAE HAMILTON

Folklorist Michelle Lanier spoke with artist Allison Janae Hamilton about her new body of work Celestine, recently on view at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York, and connections to home and the Black South. This conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

Michelle Lanier: I’m thinking about this concept of newness. And I was thinking I might bring this up later, but honestly, I have to just go in right now.

Allison Janae Hamilton: Go for it.

ML: The ouroboros—I know that this is a symbology that you’ve been living with for a while, for years now. But I’d love to hear what ouroboros means to you, and maybe what it means to you in terms of the work that you’re doing right now.

AJH: The ouroboros, yes, it’s life, birth, death, rebirth. It’s also chaotic—it’s a symbol of chaos and destruction. It’s a powerful and potent type of a symbol. I started working with it, using the alligator as a stand-in to the dragon or the serpent-like figure, bringing in my own landscapes to the idea of this chaotic death and rebirth, or this destruction and what have you.

At the time, I was thinking a lot about my home state of Florida. It’s such a vulnerable landscape. It’s right there at sea level, most of it. And I was thinking a lot of this obscuring of discussions of climate and environmental justice.

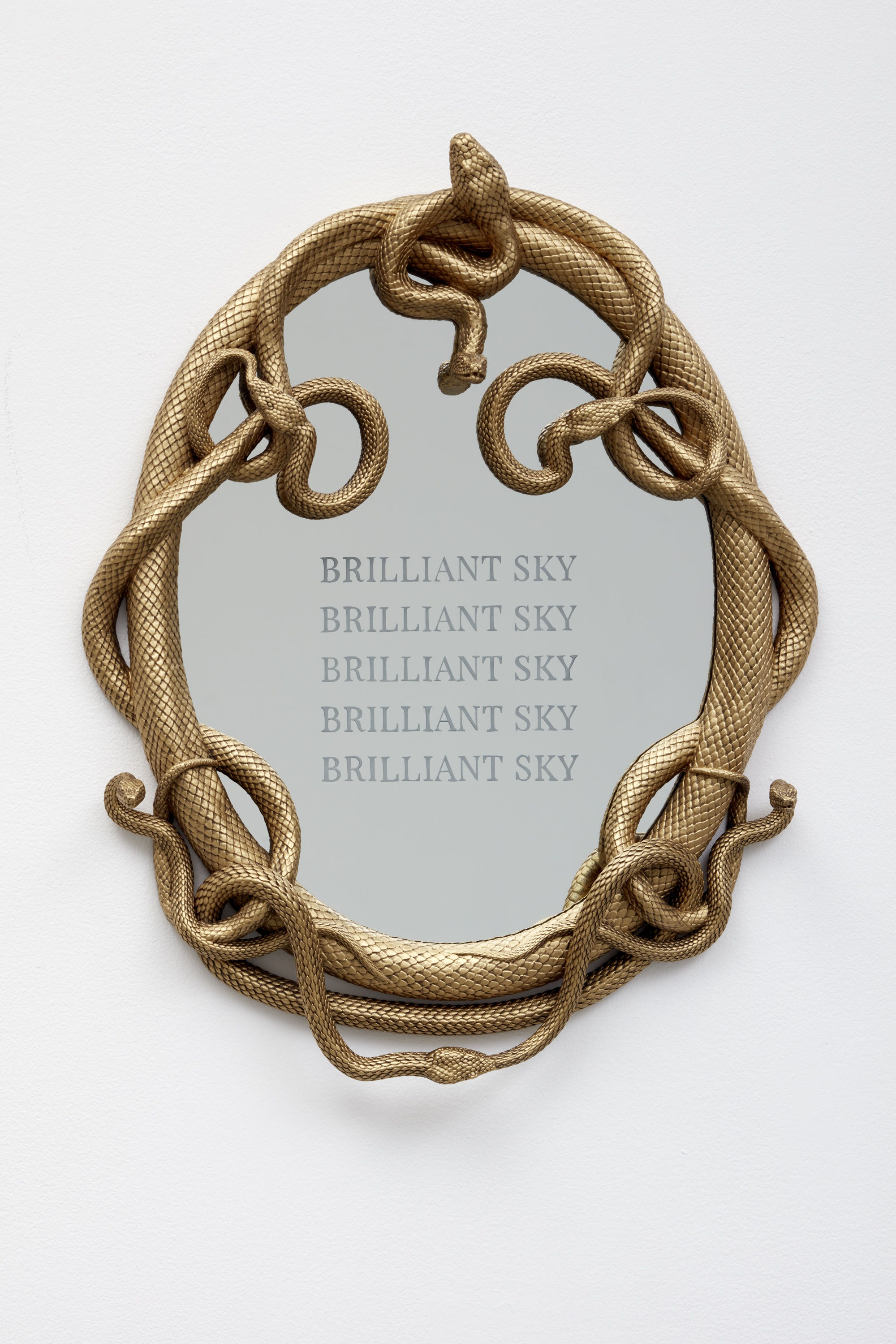

For Celestine, I’m coming back to the snake figure, which also has another element because it also shows its skin. And then the mirrored artwork is etched with the words “Brilliant Sky,” which is from Mary Ann Carroll—as you know, the only woman of the Florida Highwaymen. There’s a lot of Black southern women’s influence in the show, obviously. In my film, the voice is Candice Hoyes, an amazing opera and jazz singer from Florida. So there’s a lot of Black women’s voices and bodily tangible experience, but also it’s in the abstract.

ML: For people who do not know who the Highwaymen were, what is your telling of that collective? And then of course, I want to really amplify and illuminate Mary Ann Carroll.

AJH: The thing I find fascinating about them, given the time period, is their insistence upon the land, the landscape. I also insist upon the landscape as something that’s more than a backdrop. More than, more than, more than. It’s not this background element. It’s not this throwaway or insignificant participant. It is the main focus, the main character of what I do.

And so I think when I look at the paintings, really across the board of that collective or that school, I see narrative and I see story in those paintings. They’ve always been important to me. I have Florida Highwaymen books and things like that around the studio. They’re always important to have around me.

And then I’m thinking about Mary Ann Carroll and some of her stories of driving around Florida. I think most people, even Americans, don’t really know the landscape of Florida. I think they think of the beach, South Beach, Art Basel, Disney World. But man, it is a swamp. And so, I think about her driving through these thickets and swamps in these areas, trying to make part of her living through these artistic gestures. It’s very meaningful to me to bring her into the show, thinking about a vertical landscape. And thinking about these connections between a very grounded experience with and of the land, and also this ethereal or almost ancestral spiritual quality of the landscape as we look upward towards Celestia, or Celestine.

ML: When I think about the relationship between land and the stars and the Black South, I do think a little bit about the aesthetics of conjure, and I’m curious if that’s resonant at all.

AJH: I think that’s always resonant with my work. I think anybody looking at my work is going to find a little bit of that, a little hoodoo in there. It’s not something I’m always directly trying to do. It’s just that if I’m influenced by a particular place, I’m going to pick up what’s in that place.

ML: It’s always there in the air.

AJH: Yeah, if you know how to look for it, even though you’re not supposed to.

ML: For years, I felt like your work has troubled the false division between human and non-human characters, with the antlers, with the feathers, with the fur. Could you talk a little bit about the ways in which your work is weaving between species?

AJH: The South is a place that is often understood as past tense. In my work, especially in the beginning, I was always trying to look for ways to disrupt that, or collapse time, or expand time, or present something that was not just linked to the past. For me, these creatures became a vessel through which I could do that. I would make these different figures—human-like, animal-like. I think of them as witnesses of a long and storied landscape. But they’re also futuristic, so they’re these ways to bring in these almost infinite watchers that maybe we can imagine would have the true story of this long arc of land. You see a little bit with the masks, too.

ML: For me to be able to say, what if my face or what if my camouflage is a living ecosystem that is an extension of everything that I am and will be. I call it our ecosystem of witness that’s ripe with kindred species, companion species.

I know that you’ve listed some of the species in your conceptual language, like lemon. I’m just curious, when you think about Kentucky and Tennessee and Florida, are there certain plants that you always feel a sense of a bond with?

AJH: The thing about Florida, definitely it’s cypress, my favorite. Live oaks, Spanish moss, another favorite. Swamp pines, sable palms, bougainvillea. Part of my childhood was in South Florida, too, so shout out to that.

In Tennessee, I’m thinking dogwoods, I’m thinking lightning bugs, crickets. I grew up going back and forth between Tennessee and Florida. My family had/has a farm in Tennessee. And we raised Guinea hens. My family, many of my aunts and uncles were hunters, so we had hounds for hunting. There were always rows and rows and rows of crops.

So, I’m thinking about the wilderness. And I’m also thinking about organized flora and fauna, I suppose, if you could think of it that way. When I think of Tennessee, because we grew up going to the farm, my mind can’t help but to think about or think and feel this human interaction and cultivation of the land. We raised catfish. The main crops we had were cotton and soybeans. We had corn, we had beans, we had muscadines, we had an orchard with apples. My favorite as a kid was the blackberry vines. We had some kind of greens. But we had rows and rows and rows and rows of corn. Just a little bit of everything.

I also insist upon the landscape as something that’s more than a backdrop. More than, more than, more than. It’s not this background element. It’s not this throwaway or insignificant participant. It is the main focus, the main character of what I do.

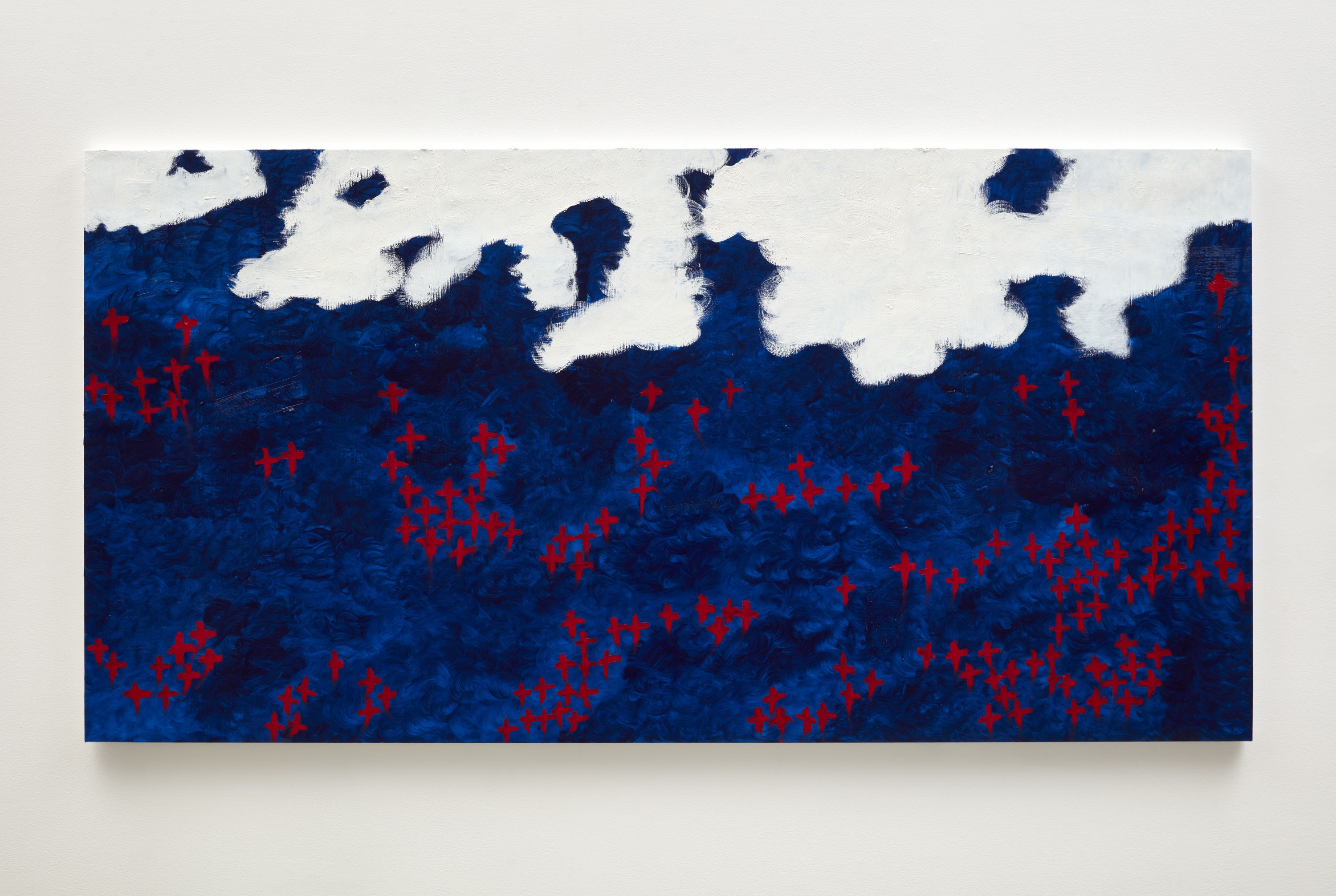

ML: There’s absolutely a reverberation. Because I see a cropping, even in your orchestration of the Xs on your signs.

AJH: Oh, yes, they are. I have family photos all over my studio, and sometimes I look at the architecture of the roof of a house or something with the rows of the farm and I use that as a rubric for these constellations. Because some of them are made up. I have used Sirius and Dogon cosmology and I’ve used Western constellations. I’ve used all kinds of things as models. But now I sometimes use the architecture or the shapes of the compositions of some of the portraits in my family photographs I have in the studio just to give me something to tether onto in terms of structure.

ML: I’ve been really struck by the power of how artistry has shown up in terms of your new life as a mother. I didn’t know if there was something you wanted to say about that before we dive deeper into this show?

AJH: I started painting when I came back from my parental leave. When you become a new parent, everything in your world feels so new. Painting was something that I had always wanted to do. It just was a medium that I hadn’t gotten to. I didn’t paint in art school, not formally. I’d been doing sculpture and film and photography, and it was in the back of my mind to get to. Then I came back to the studio after having taken time away to have my daughter. Everything felt new in the other parts of my life. So, I said, “Well, what better time than now to shake it up in the studio, too?”

In other ways, I think I’m just very much myself and the most myself. I think that my ideas flow quicker, more efficiently, because they have to. So, we’re churning out a lot of work at the studio. We’re making way more work than I was making before. It’s a busy, wild circus. But I love it.

ML: I wrote this phrase when I was thinking about your work—there’s an intimacy of light beheld by the eyes. I know that you are contending that the sky is personal. Could you crack that open for us?

AJH: I think it is. Whenever there’s those moments—Oh, tonight there’s going to be a supermoon, or Oh, there’s an eclipse—it feels collective. Everyone goes outside to experience those moments together. But there’s a human impulse to want to look up. There’s a calming similar to water. There is an awe.

The actual word awe is very powerful. We throw around awesome and things like that, so we’ve watered down the language. But truly, those moments of awe are special, and they connect us to the natural world in ways that I think are very personal. And so, I think there’s something very personal about water and about the sky. They both have a way of calming us, grounding us, and letting our equilibrium find itself.

ML: Is there a hope that you have in terms of the affect of this work, for your viewers?

AJH: Well, yes and no. I like the viewer to have their own journey through the work, through each body of work. I try not to hold their hand too much through it. I try not to force my ideas too much. I try to present my ideas emotionally, and they can, well, move in and out of intensity and quiet. Move in and out of intimacy and overtness.

There’s definitely a link between what’s happening on the land and then the possibilities or the imagination that comes with looking upward.

ML: I’m taking it as an invitation.

AJH: An invitation, yes.

ML: I’m naming that because I am also of what I call the Black Femme South. I know this work is for anyone who would encounter it. And as a person who’s of the Black Femme South, I know that there’s also something in this that is deeply tied to my demographic, which feels like a gift.

AJH: Thank you for saying that. I’m making a body of work—a lifetime of work—that is an exploration and experiment with what happens if we center the landscape in our ideas of the social, the political, and the cultural. And me being who I am, I’m going to draw from the landscapes that I know and draw from the experiences that I know best. So yes, the region is going to be the region that I know. The experiences, the voices, the figures are going to be those that I know—and a celebration of that.

It’s also an exploration of broad themes of land, climate and environmental justice, and all these things that that are very, very important in the Black Femme South. These are key critical issues. I’m hoping that through my work they’re seen as issues important to these demographics. They’re seen as a Black feminist issue. Landscape, climate change, these are issues that are very important to Black women, for Black women, and that impact Black women in major ways.

ML: I love every bit of this. It really is such a joy to witness. Your work is a source of inspiration for my thinking and my writing as a Black geographer, as a folklorist, as a womanist cartographer, as a womanist cosmographer. And your deep and profound respect for land and these ecologies is something I join in solidarity.

Allison Janae Hamilton has exhibited widely across the United States and abroad. Her work has been the subject of institutional solo exhibitions at the Georgia Museum of Art, the Joslyn Art Museum, Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), and Atlanta Contemporary, as well as a commissioned solo project with Creative Time. Select recent group exhibitions include A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration, organized by the Mississippi Museum of Art and the Baltimore Museum of Art; there is this We at Sculpture Milwaukee; The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; Shifting Horizons at the Nevada Museum of Art; Enunciated Life at the California African Art Museum; More, More, More at TANK Shanghai; and Indicators: Artists on Climate Change, Storm King Art Center. Hamilton holds a PhD in American Studies from New York University and an MFA in Visual Arts from Columbia University. She lives and works in New York.

Michelle Lanier is an AfroCarolina folklorist and writer rooted at the crossroads of many Souths. A keeper of memory, she stewards 27 historic sites, and regularly asks this question: “What and who did the land witness?” Lanier teaches as a unionized fellow with the Center for Documentary Studies and the Department of African and African American Studies at Duke University. Inspired by the footfalls of Harriet Ann Jacobs, she is pursuing a doctorate in Geography and Environment, which will be her second terminal degree from UNC-Chapel Hill, the first being in Folklore. Published by Oxford American, ACME, Bitter Southerner, UNC Press, MIT Press, and Open Book Publishers, she has also contributed as both writer and collaborative guest editor for Southern Cultures.