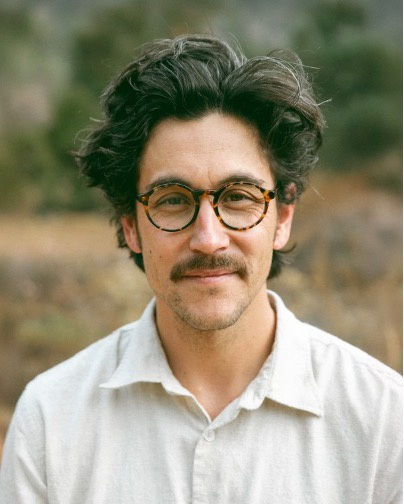

BY MATEUS NUNES

In retaliation to the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States government imprisoned some 120,000 people of Japanese heritage (more than 70,000 of whom were U.S. citizens) in ten internment camps mostly built in the Western United States.1 Photographic archives of the concentration camps—which were euphemistically called “War Relocation Centers”—are stored in the Records of the War Relocation Authority of the U.S. National Archives in Washington, D.C., an archive that Los Angeles-based artist Dashiell Manley began diving into 15 years ago. Manley was principally seeking images of his grandmother, great-uncle, and great-grandparent, who were imprisoned in Tule Lake in Northern California, the segregation center situated closest to the West coast, straddling the California- Oregon border.

In spending time with the archive, Manley was struck by the propagandistic reach of the archival images, some of which were taken by renowned photographers such as Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, artists who were responsible for idyllic signifiers of the American West: caricatured wide-open landscapes, profitable boomtowns, and rugged miners. Manley leans into dynamics of sociopolitical control in historiographical and media structures. Present within this particular archive is a false idea of life in the concentration camps. One photograph features unsettlingly cheerful smiles of children dressed in festive kimonos, for instance—a contrived, violent, and unjust visual retelling of the history of the Asian diaspora during a period marked by racial prejudice and wartime hysteria. The impact of such images continues to echo through history as a form of racist propaganda.

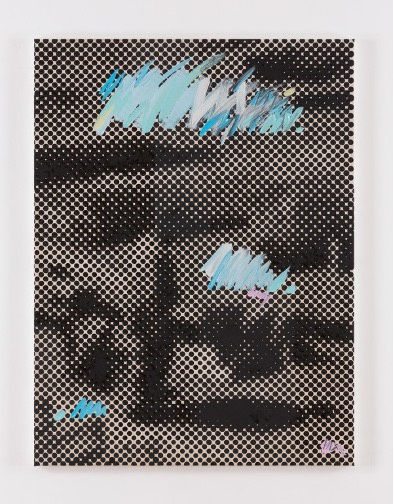

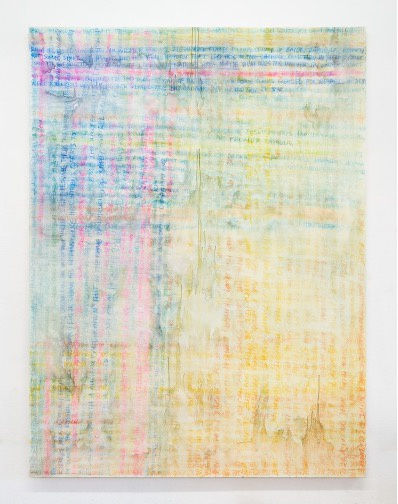

The confrontation of preestablished epistemological systems has been central to Manley’s work since the beginning of his career. With a deep theoretical foundation influenced by American conceptual and post-conceptual art, he began working in video and installation, though for over ten years, Manley has turned to painting to critically question language and information. In his series The New York Times and Elegy (both 2014–present), the artist addresses late capitalism’s barrage of information. Appropriating the text of the newspaper’s front pages into vibrant watercolor abstractions, The New York Times undertakes the unsurmountable retention of a daily attention span and a consumerist convention of encapsulating information published in circadian doses. Elegy, by contrast, bids farewell to this overwhelming influx—the abstract paintings are made by employing ceaseless, meditative gestures with vivid oil paints across the canvas as if in an effort to clear away the clutter of excessive information.

Manley utilized desynchronized archival images of the Tule Lake concentration camp alongside his own photographs of cherry blossom trees and monochromatic blocks in the two-channel slide-projection work pleasant countries (Tule Lake) (2024), included in his latest solo show, Tule Lake, on view last summer at Jessica Silverman in San Francisco. pleasant countries highlights the staged aspect of the archive through intentional pairings—in the projection, the smiling children in kimonos appear alongside a photograph that depicts forced labor in a barren desert landscape.2 The photographs of cherry blossoms (which incorporate traditional Japanese symbols, such as ikebana and Sakura branches, that resonate with themes of resilience and beauty) serve as meditative respites from this devastation. Meanwhile, the monochromatic fields, derived from color samples of the flower photos, represent a sense of close, introspective observation. Displayed on a white wall, these images emitted from two analog slide projectors placed side by side on the same plinth. Despite their pairing, the projectors were independent—although they played simultaneously, the images were always slightly out of step with each other. This tottering cadence, oscillating between information overload and respite, mirrors the tensions between violence and resistance, histories that overlap and yet can be retold through wildly disparate lenses.

Months after meeting—first in São Paulo and then in New York—Manley and I spoke several times via video call about his practice. In this conversation, we focused on pleasant countries and discussed the intersections between archival violence and the fictionalization of images.

Mateus Nunes: pleasant countries was inspired by your archival research, which was a genealogical investigation into your family’s experience during internment. You sought records of your relatives at Tule Lake. How were you impacted by these archives?

Dashiell Manley: I’ve always been interested in [the history] for several different reasons, but it wasn’t until recently that it became personal, or maybe I let it become personal. I initially approached it with a kind of suspicious amount of emotional distance, instead focusing on details of specific photographs relevant to my work at the time. I think it was probably a way of distancing myself from having to sit with the idea that my grandmother and other family spent time in these camps in their youth. It was always a kind of gray subject—not necessarily taboo, but not something that was openly discussed. I returned to the archive a few years ago, kind of in tandem with personal explorations I was doing at the time in therapy, and I started to wonder if I might find some images of my grandmother or other family members in the background of some of these pictures. I haven’t, but projects have sprouted through this process.

MN: And on the personal level?

DM: On a personal level, the exploration of this archive has been exhausting and uncomfortable. I think one of the most impactful moments came when I stopped looking at these images as historical artifacts—at least in terms of the objects themselves being a kind of document of something, a document of Japanese American internment—and instead started looking at them as documents…not so much of everyday life inside the camps [but as] documents of this kind of propaganda machine that was swirling around America at the time.

I haven’t found photographs of my family there, for instance, even though they were in the Tule Lake camp. [I wanted] to reflect on how these temporary spaces of detention are a gray area: this ideological, social, philosophical, and moral area that allows us as individuals, and certainly as a society, to excuse certain acts, which can also be a historiographical, memorial blank space. It’s temporary, it’s transitional, so, therefore, we don’t need to take stock of or audit the significance of it. Much like a refugee camp or a temporary prison, right?

And artistically speaking, the archive has been really generative. I’m kind of at a point where I have more ideas for projects than I will ever have time to produce. And that’s a really comfortable space for me in contrast to the discomfort [the archive] produced early on.

MN: In pleasant countries, you combine the images of the archival photos with images of flora—you’ve mentioned that your grandmother was fond of ikebana. But you also pair them with monochromatic blocks. For you, how are these different elements in dialogue with each other?

DM: I feel like I need to go back a little to answer this question. With The New York Times paintings, I found myself in a state of overwhelm, overloaded by ingesting that much textual information so closely for such a short and dense period of time. The solution to this feeling was the Elegy paintings, which I came to as a kind of a joke, or by accident, but it was essentially like…“I’m not a painter, I’ve never been a painter, I have this oil paint, I have these canvases…I’m going to make a really stupid painting.”

MN: It’s curious that you mentioned that you thought that you were not a painter. I always saw your work as that of a conceptual artist, and when you painted, it was clear to me that it held a robust conceptual background that would stand behind the pictorial image, and that the medium—be it painting, installation, or video—was just a means of communicating this conceptual argument. But let’s go back to the different nature of the images.

DM: I agree with you, it’s nice that you see the work this way because I also believe in this. But okay, going back to the images…I started making these repetitive marks. And what came from that was these meditations, right? This period of repetitive meditation presented an opportunity to get rid of that information and those feelings of overwhelm with information.

MN: As a reprieve?

DM: Yes. I’ve often looked to use a similar strategy in other works that I make. With these works, in dealing with these images [from Tule Lake], I wanted them to be, particularly in the projection work, a reprieve from the weight of history. And so I started taking these walks. As I was working in the studio, I would work for hours. It was too physically and mentally exhausting, [so] I would go take a walk, and at some point, I started taking pictures of flowers. I’ve made a massive folder of pictures of blossoms.

When I was thinking about the projection work and thinking about the painting and thinking about my practice as a whole, again, this idea of beauty came up. I thought that I could point to that or hint at that by allowing these images of flowers into the narrative of the projection work so that you would be confronted with the image and then you’d be confronted with this non sequitur in a way, this idea of beauty. And then the color…it’s essentially just a color sample from the image of the flower. It’s like a color that’s contained within. I saw that as this kind of zoom-in, while the historical image is almost like a zoom-out. The image of the flowers is bringing it back to present day and the image of the color is this extreme, almost impossible, zooming in.

MN: This question may be a little psychoanalytic, but you always mentioned that your grandmother, when she was talking about her memories from the camp, always fled from them, as if avoiding them to protect herself. Do you think that going into the images of flora is a similar strategy of “maybe if I don’t remember it, I can move on?”

DM: Yeah, I know what you’re saying. I think that this is a complicated question because I believe that to answer “yes” would be to acknowledge that the images from the archive [are] something other than propaganda. It became very clear to me that the images in this archive are not in fact historical documents. They’re completely staged and coerced.

I don’t want to get too into theoretical questions about photography and what its limits are, but yeah, I feel like to acknowledge a move away from the images of the camps would be to give those images a power that I actually don’t think they have because they’re propaganda images: coerced, staged.

MN: Like the flora photographs?

DM: Yes! I think the flora photographs point to this…very basic idea of our need to question what we’re looking at to begin with. Because it offers…a seemingly unrelated image, but it’s kind of a more true image, right?

MN: Sure—and the projection subtly superimposes these layers of archival truth and documentary with fictional narratives full of fallacies, right? It’s as if you’re attesting that these historical narratives are an amalgamation of many things.

DM: This is a bit of a tangent, but one of my favorite things in the world is when I’m driving my car and I’m at a stoplight turning and I have to put my turn signal on [and] I’m playing music. There’s this moment where the rhythm of the clicking of the turn signal matches up with the rhythm of the music.

I derive such a deep sense of satisfaction out of these. The dual projections [playing] out of sync…they provide a very similar thing. There’s a sensory experience you can have with the rhythm of these projectors falling out of sync and then back into sync. I think it can be read conceptually in the sense of like, this can be [multiple] dimensions that coexist.

This interview was originally published in Carla issue 39.

Dashiell Manley (b. 1983, Fontana, CA) is a Japanese-American artist who employs a labor-intensive and meditative practice to create impasto abstract oil paintings. Informed by an abiding interest in film and photography, Manley works with conceptual frameworks to examine language, memory, and history. His colorful, highly textured abstractions operate as psychological landscapes.

1. These actions were materializations of Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorizing the Secretary of War and the Military Commanders to exclude, remove, and incarcerate individuals seen as a threat to homeland security in prescribed military areas. See: Executive Order 9066, February 19, 1942; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/executive-order-9066.

2. Manley believes that “any actions undertaken at the camp—even (the Japanese American detainees’) presence there—are a kind of forced labor,” reckoning that his position is “not necessarily accurate to the dominant historical record of the events.”

Mateus Nunes, PhD is a São Paulo-based writer, curator, and postdoctoral researcher from the Brazilian Amazon.