BY GRACE EDQUIST

When I visited the Manhattan studio of the artist Allison Janae Hamilton recently, I was struck by the many family photographs pinned up around her workspace. There were dozens of them, dating as far back as seven generations ago. All four of her great-grandmothers were there: Della, Maria, Alice (who she’s named after), and Ola. At one point Hamilton pointed to a pair of portraits of her great-aunt she took when she was 12—some of her earliest artworks. “I would take the film and develop it in my little darkroom in middle school,” Hamilton told me. “I was obsessed with it as a kid.”

Surrounded by all these family photos, she says there’s a “haunting, ancestral thrust” that infuses her practice. It comes not just from the people in the photographs, but from the land. Most of the photos were taken on her family’s farm in rural Tennessee. Hamilton grew up in Florida but spent a lot of time on that farm as a kid, helping with each planting and harvest. “My experience of Black womanhood is really bound up with the land. My aunts all hunted and fished and farmed, and I grew up around that culture,” she says. “Which is not often the first assumption that pops into mind when people think about Black womanhood.”

Hamilton has long tapped the landscapes of her pan-Southern upbringing to inform her work, and for a new solo exhibition at New York’s Marianne Boesky Gallery, called “Celestine” (through March 8), she takes a particular point of view: looking upward. This show, her second at Marianne Boesky, sees Hamilton playing with familiar motifs in novel ways across film, painting, and sculpture. “The theme is sort of like vertical landscapes: the soil and then the stars,” she says.

Perhaps the thesis piece is Celestine (Florida Storm), a 12-minute time-lapse of the night sky filmed in Hamilton’s home state. As stars skid across the screen, singer (and fellow Floridian) Candice Hoyes recites the lyrics to “Florida Storm,” a hymn written by Judge Jackson about the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926. The song was published in 1928—the year the Okeechobee Hurricane brought even more devastation to the area. The Okeechobee storm especially impacted Black migrant workers, thousands of whom were killed and buried in unmarked graves.

The film is a meditation on the interconnected forces that continue to shape our world—climate, power, racial injustice. “You think about these histories of these natural disasters, and then combine those with these human-made disasters…how they land on top of each other, and how these storms are actually political things, and social things,” Hamilton says. As Hoyes croons “The people cried mercy in the storm” over and over again, the pain of catastrophe washes over, but so does a sense of hope.

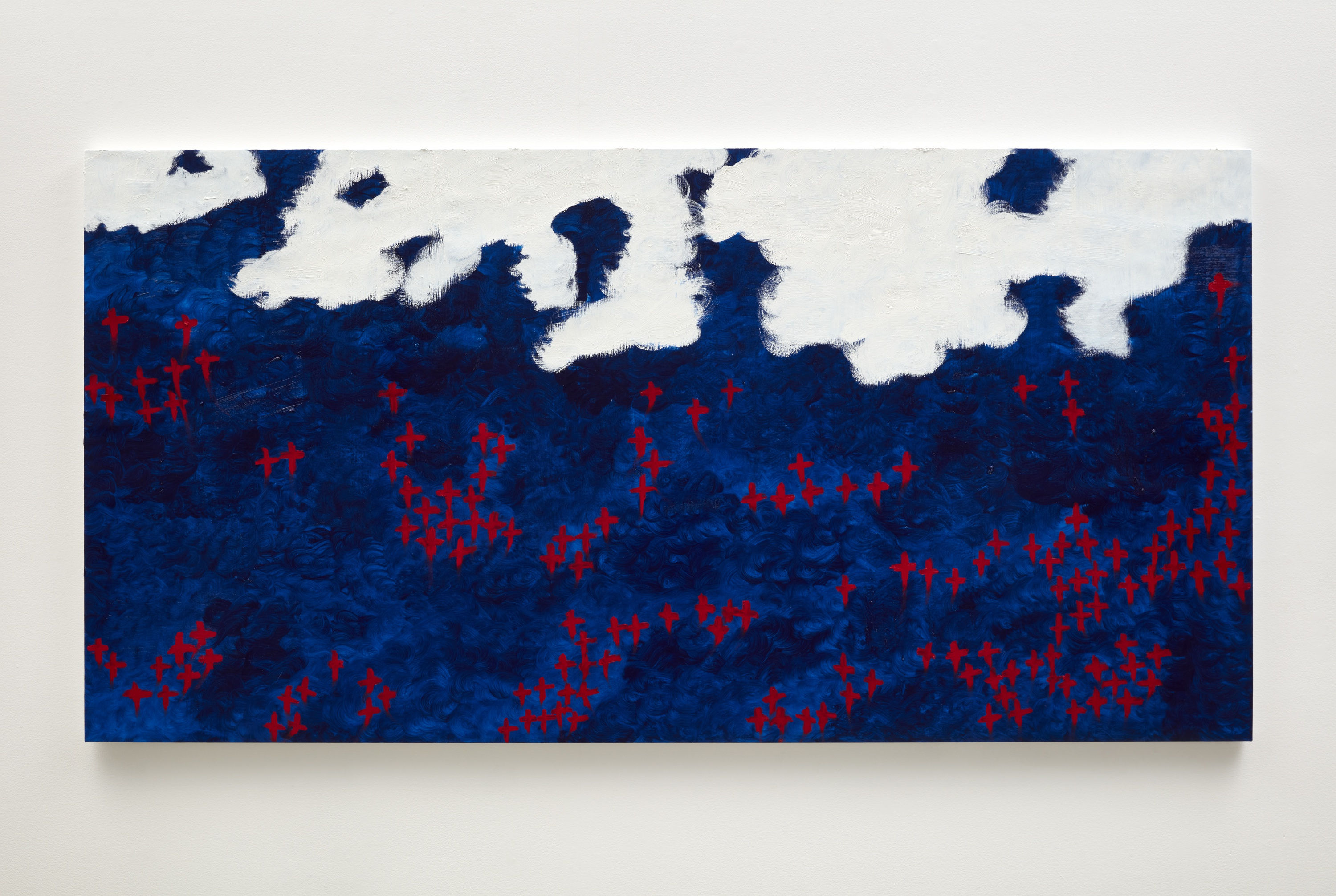

The three large-scale paintings Hamilton made for the show again reference the night sky. They mark the first time she has worked with oil on canvas; previously she’s painted on wood or other found objects. “When I came back to the studio after having my child”—her daughter is now two—“everything felt so new. My life felt new. Everything was a learning curve. So I got back to the studio and said, ‘I think I’m going to paint now.’”

Each painting is a mash-up of constellations pulled from mythology and her own imagination—stars rendered as crosses in varying shades of blue, red, black, and white. The paintings have stillness to them, a reverence for the antiquity of the cosmos.

“Celestine” also includes three fencing masks—objects that have featured in Hamilton’s work for years—but for the first time she has cast them in bronze. As with her earlier masks, each is poetically adorned: one with grapes, one with antlers, and one with flowers. But instead of mounting the masks on the wall, as she usually does, the bronze masks are hoisted on posts atop plinths, less like sentinels watching over the space than captains asserting their presence.

Hamilton began working with these types of masks after seeing a photograph of Black American soldiers fencing during WW II. “I was thinking about how they would go out and fight in these wars for our country and come back to the same kind of brutal conditions that were there when they left,” she explains. She started collecting the masks and using them as props in photographic works. Eventually, she saw them as their own standalone artworks, and her embellishments grew more elaborate. “The masks were kind of stand-ins for a body,” she says.

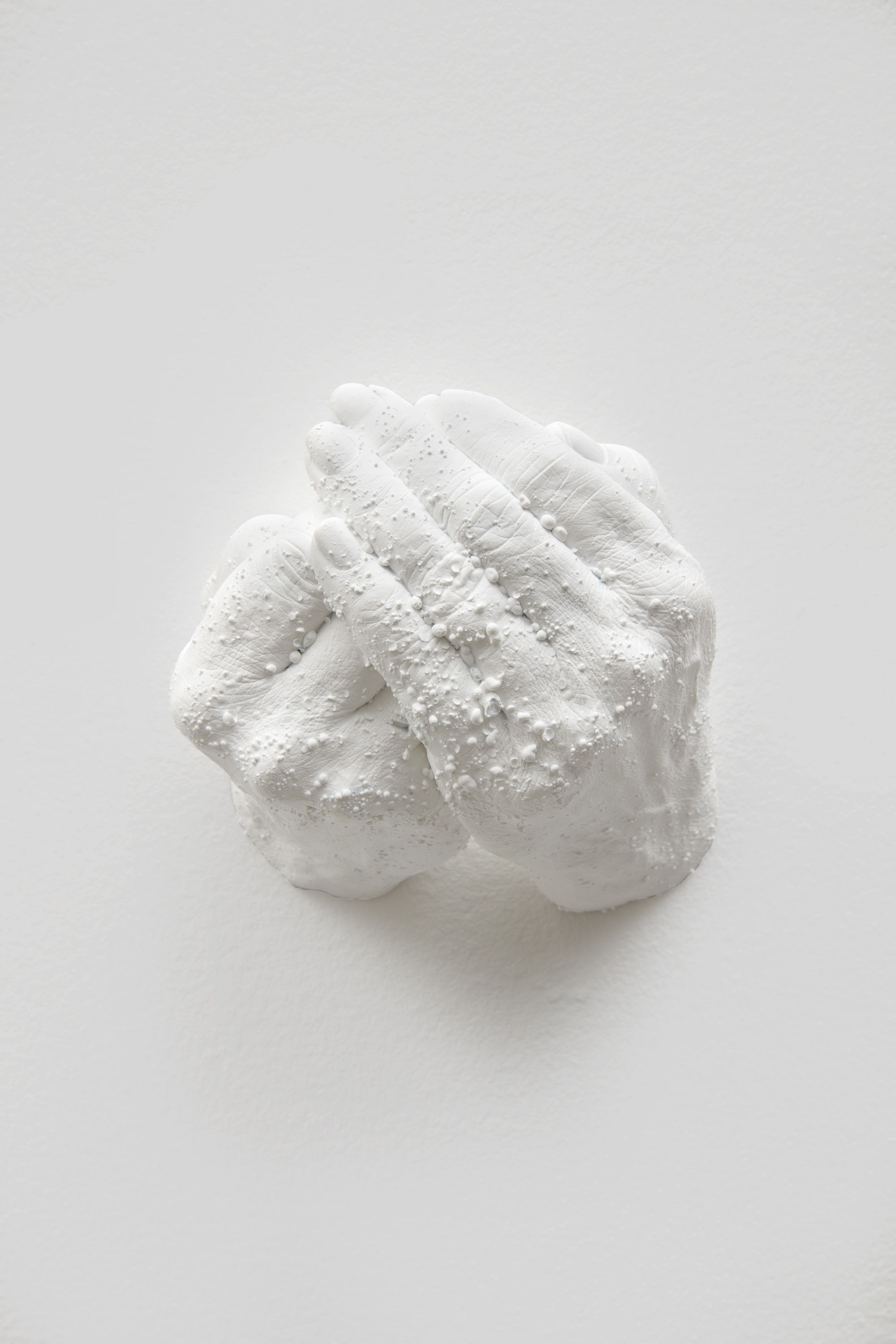

Other bodily stand-ins at the gallery take the shape of hands, cast from colleagues and friends of Hamilton’s like Deborah Willis and Schwanda Rountree. The gestures of the plaster-cast hands (cupped open, half praying, the fig symbol) nod to the African diaspora, but it is the tenderness of casting parts of the people close to her that makes these pieces so moving.

The world is dizzying, especially lately. We are on shaky ground. Hamilton’s work in “Celestine” reminds us that reverence for what came before us—for the people and the land—doesn’t only mean to root down. In the fight for a better world, we must also look up.