BY ALEX GREENBERGER

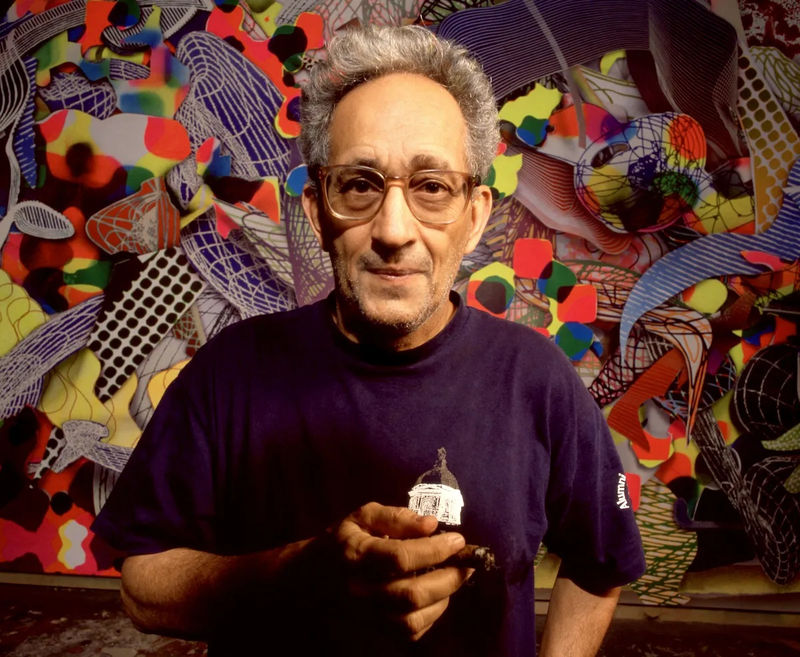

Frank Stella, an artist who brought abstraction into brave new directions, defining an era with his “Black Paintings” of the 1950s, died on Saturday at 87. The New York Times reported that he had been battling lymphoma.

Stella was among the many artists who responded to the growth of Abstract Expressionism in the postwar years. His spare paintings, made as a riposte to that movement, were particularly challenging, since they contained no color at all and were not intended to provide visual stimulation in any way. As he famously told the Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd, speaking of his own work, “What you see is what you see.”

He would come to redefine painting over and over again during the 1950s and ’60s. In a subversive move, with his work having approached a zero-degree form of abstraction, his paintings turned maximal, enlisting eye-popping combinations of colors arrayed in dazzling patterns. He also produced shaped canvases that broke the medium from its rectangular confines and moved it into the realm of sculpture.

In the decades since, Stella’s art has grown bigger and bigger, as he began making sculptures that are massive in scale. By turns gaudy and gorgeous, these sculptures assault the senses with their unruly combinations of steel, fiberglass, and other materials.

Critics have not always responded positively to Stella’s art after the 1960s, but his oeuvre has been considered integral to 20th-century American art history anyway. He was given a retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum in 2015.

Adam Weinberg, who curated that Whitney show, wrote in the show’s catalog that Stella stood out for “his impulsiveness, willingness to take risks, desire to be separated from the group, and to do things his own way; his commitment to using the tools at hand; and his persistence in solving a problem.”

“A giant of post-war abstract art, Stella’s extraordinary, perpetually evolving oeuvre investigated the formal and narrative possibilities of geometry and color and the boundaries between painting and objecthood,” said his New York representative, Marianne Boesky Gallery, in its announcement of the artist’s passing.

Stella’s “Black Paintings” remain his most famous works. In these paintings, Stella used a mostly black palette, dividing his void-like expanses with white lines that were applied using geometric systems. With their mathematical logic, their precise brushwork, and their generally unappealing look, the “Black Paintings” marked a sharp break with Abstract Expressionism, which privileged randomness, artistic originality, and grand statements about the nature of humanity. By contrast, the “Black Paintings” seemed intentionally to say nothing at all.

The “Black Paintings” were provocative, and not only because they looked so different from almost anything else up to that point. One of the more famous ones, Die Fahne hoch! (1959), has a title that translates from the German to “Raise the Flag!,” an allusion to a Nazi chant. That this disturbing reference point contains no explicit relationship to what is represented only heightens the canvas’ unfeeling quality.

That work and similar ones appeared in “Sixteen Americans,” a 1959–60 Museum of Modern Art show that also featured art by Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, and others, all but affirming Stella’s status as an important talent worth watching. He was just 23 at the time.

Just several years earlier, Stella had been a student at Princeton University, painting unnotable Abstract Expressionism lite. He had begun to feel fatigued with anything related to that movement, and to feel dispassionate toward painting altogether. But he did not want to divorce himself entirely from art history, a field to which he felt an allegiance of a sort.

He looked to Manet and Zurbarán, and found aspects in their work that he wanted to emulate. As Stella himself once put it, “You can’t be a good competitor … if you don’t have some real understanding and respect for your opponent.”

Born in 1936 in Malden, Massachusetts, Frank Stella was instilled with a fondness for art early on by his parents—a mother who painted in her spare time and had gone to design school, and a father who was a gynecologist. Stella attended the Phillips Academy in Andover, taking art classes alongside future stars such as Hollis Frampton and Carl Andre, whom he did not know well at the time but would later count among his close friends.

Stella did not consider art a viable career, so he attended Princeton’s history program, intending to focus on the Middle Ages. He was able to take art history classes, however, and was given an education in European painting and contemporary developments in the New York scene. He graduated in 1958.

The same year, Stella saw Jasper Johns’s flag paintings at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York and was bowled over by them as an appropriate form for the medium. He started the “Black Paintings” not long after, and accepted the invitation to participate in MoMA’s “Sixteen Americans” at Castelli’s urging.

The “Black Paintings” may have seemed risqué for the time, but Stella did not pull back in his works to come. He began to use aluminum paint, which, unlike oil, was not a common medium for art—it was associated more with coating radiators and the like. Stella said he adopted it because aluminum paint was “cheap and available.”

Ever the fearless artist, Stella was never content to be formulaic in his art. His shaped canvases of the ’60s departed from the “Black Paintings,” continuing to rely on striped compositions but swapping out those dark tones for dramatic colors. These canvases are off-kilter, with arced edges and diagonal swatches seemingly cut away. The “Protractor Series” of the late ’60s brought that body of work to its apex, filling semicircular canvases with interlocking warps of orange, black, blue, and more.

Then Stella veered in an entirely different direction, making baroque painting-sculpture hybrids that complemented the shaped canvases’ oddball contours with elements that fly all over the place. Some were vaguely allusive: he did an entire group of pieces in the ’80s devoted to Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, sometimes including wavelike parts that played host to abstract elements. But many more works were less representational.

Many observers did not care much for these pieces, viewing them as a form of selling out. Art historian Douglas Crimp, for example, once labeled similar artworks “pure idiocy,” writing that “each one reads as a tantrum, shrieking and sputtering that the end of painting has not come.”

That did little to bruise Stella’s ego. “I was brought up with the critics and with art history so that’s the only world I knew,” he said in a 2015 ARTnews profile. “So, on again, off again, that didn’t much matter to me. That was their job, and I had my own job. I was pretty comfortable.”

Right up until the end, Stella made gigantic works, some of which enlisted digital technology in their production. He would scan objects that intrigued him and then gradually expand them to towering proportions.

These have often seemed like bizarre gestures for an artist whom many have claimed once tried to kill painting, but all these works were tied together by a desire to get in touch with our reality. His scanned objects were sometimes ones he in encountered in the wild—a seedpod found at the New York Botanical Garden, for instance; his “Black Paintings” were intended to pull their medium back down to earth. Speaking of his choice to begin using aluminum paint, he put it simply: he was interested in “the facts of life,” he said.