BY BETSY SUSSLER

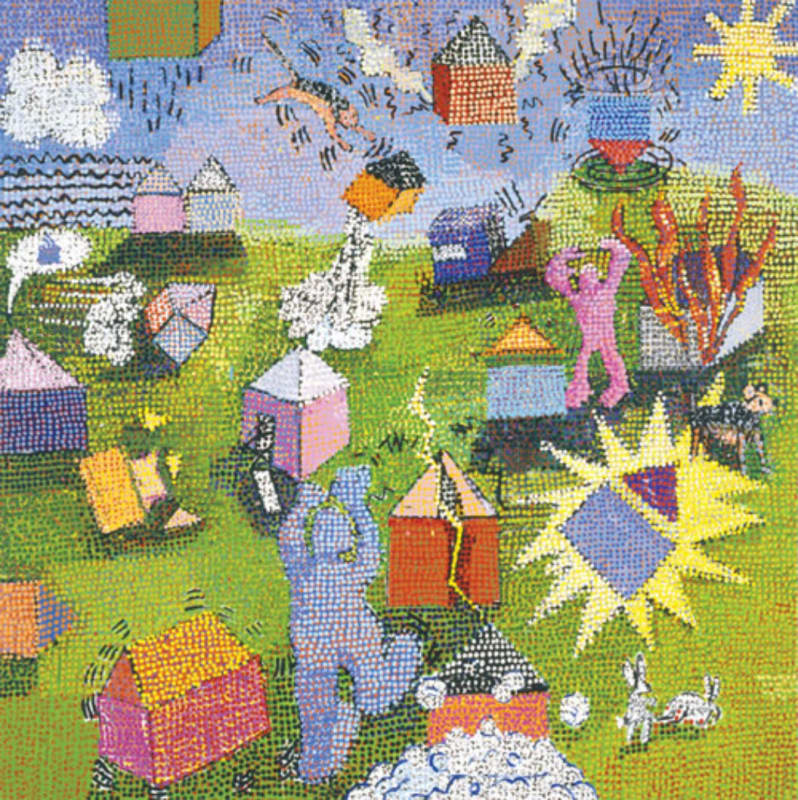

Bartlett has used the serialization of geometric forms, familiar objects that recall the ideal American homescape—a house, a tree, a white picket fence—along with literal painterly shapes, a line or a brush stroke, to create paintings of incremental, seemingly endless possibility. Her paintings with three-dimensional objects have reinvented the mural. More recently, a particular narrative has evolved—contained in traditional stretched canvas—a cumulative transformation of combines that hints at a darker, perhaps imperfect world, where nightmares melt into cartoon dreams, referencing Gorky’s influence. In their long association as peers and as friends, Bartlett and Murray have occupied parallel worlds; they have watched each other’s work develop over 30 years.

What follows is an oral history of sorts, of two painters’ progress.

—Betsy Sussler

Elizabeth Murray: I met you in the fall of 1962, at Mills College, in Oakland, California. You were a senior and I was a first-year graduate student. I remember the first time I set eyes on you: we passed each other on the road, and you looked at me with a quizzical, curious expression and then walked on by with your fuzzy beehive hairdo. What were you thinking about in the fall of 1962?

Jennifer Bartlett: Being an artist, Ed Bartlett, Bach cello suites, Cézanne, getting into graduate school, getting to New York, Albert Camus, James Joyce. I’d drawn constantly since childhood: large drawings of every creature alive in the ocean; Spanish missions with Indians camping in the foreground, in the background Spanish men throwing cowhides over a cliff to a waiting ship; hundreds of Cinderellas on five-by-eight pads, all alike but with varying hair color and dresses.

EM I remember one painting from your Mills college days; you were very proud of it. We had both just discovered Gorky. Your painting was little, in grays and blacks, and it looked—

JB Like Gorky.

EM Who else interested you?

JB In high school I went to see a Van Gogh show at the Los Angeles Museum; it knocked me out. I had little exposure to art but knew I was going to be a painter. My mother had one art book at home, with Cézanne, Picasso, Van Gogh, Manet. I thought it would be possible for me to do that. I also wrote poetry.

EM What were your favorite books?

JB Anything that had nothing to do with Long Beach, California. Dostoevsky, The Alexandria Quartet, True Confessions magazine, Seventeen magazine, the Oz books, T. S. Eliot, Stephen Crane, Nancy Drew, Hendrik Van Loon, a book on color theory. At Mills I picked up L’Etrangerby Camus, and my course was determined: art had to be dark, spare and serious. I’ve yet to achieve one of these goals.

EM Why did you feel that way? You turned me on to Lawrence Durrell.

JB My own childhood was dark and mysterious. The books, movies and art I liked had complexities that I could identify with, and that were not part of the milieu in which I lived. Truffaut, Godard, Fellini, Jean Genet, Violette Leduc, John Cage, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charlie Mingus, Mondrian, Miró, Kandinsky. I felt there was a chance I could do this myself.

EM In 1963, you left Mills and went to Yale. Who was there?

JB You and Carlos Villa were the first real artists I’d met who had been in a community of artists. Yale was such a community. All ambition, all the time. Richard Serra, Brice Marden had just left, Nancy Graves, Jon Borofsky, Chuck Close, Michael Craig-Martin, Jan Hashey, Janet Fish, Sylvia Mangold, Jenny Snider—whose brother-in-law was Joel Shapiro.

EM The next time I saw you, you were a different person. I visited you in New Haven from Buffalo, where I was teaching. You came downstairs and opened the door and there was this teenybopper girl in a miniskirt, a little Beatles hat tilted on your head. You had left Mills far behind. You showed me these huge pictures. They were completely ambitious and quite different from the little Gorky imitation. Something big happened to you there.

JB Yes, I’d walked into my life.

EM And Jack Tworkov?

JB Yale was conservative as an art department—not the students, but the faculty. Jack brought in famous artists.

EM Younger artists.

JB James Rosenquist, Jim Dine, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Alex Katz, Al Held.

EM What did you learn from these people? Or was it just the idea that they were

such fabulous artists?

JB With New York City one and a half hours away, I was seeing art, and at Yale watching the people who made it.

EM To paraphrase Jimi Hendrix, you were experienced.

JB I was away from California, and it was easy to be what I guess I always was. I did big paintings right away.

EM I remember that feeling of arriving in New York, landing on the streetcorner and thinking, This is where I belong. It felt like I fit into something that I wanted to be or that I could be.

JB I married Ed Bartlett and got a loft in New York, 175 dollars a month for 2,500 square feet. I commuted from New Haven to New York to the University of Connecticut where I taught, slept in my office, then back to New Haven.

EM That was the Greene Street studio? I remember it well.

JB I was there for 13 years. Jon Borofsky was across the street. Richard Serra and Nancy Graves were married. Joel was married to Amy Shapiro. You and Don Sunseri were married; Chuck and Leslie Close and Joe and Susan Zucker lived around the corner. With Chuck, Joe, and me, there were lots of dots on Greene and Prince streets.

EM Do you remember the first work you did in the loft?

JB I’d write out a list of ideas for work, and beside them I’d put down the artists I felt owned them. Art at that time had to be new. One had to make the next move. I did the things on my list that other artists didn’t want to do. They were conceptual, off base, not correct. They involved committed trips to Canal Street for rubber plugs, plastic tiles, hanks of rope, red plastic teapots, which I would subject to various ordeals: baking, freezing, dropping, painting, smashing, et cetera.

EM Right, I remember that. But you just said something very interesting—you sort of muttered under your breath, just now, That’s how the plates started. I want to ask you about that. But I also want to remind you of your birth present for [my son] Dakota. You gave him these plastic boxes filled with incredible things, little tiny shapes that were like asteroids. There was a whole world, a universe in those boxes.

JB They fit in small steel drawers; I made a written key describing the items in each one.

EM It reminds me so much of the unfolding of the metal-plate pieces, where you develop incremental variations using these 12-inch squares. Looking at your studio right now, it’s the same issues and ideas of the world, and colors and shapes that are all still there. All compartmentalized.

JB Yes.

EM So you just said that that’s how the plates started.

JB Do you remember two things that were happening then? Process art, where everything was on the floor—

EM Who were the process people?

JB Alan Saret, Richard Serra, Carl Andre, Joel Shapiro, Barry LeVa, Mel Bochner, Robert Morris, with his felt pieces, Robert Smithson. The other thing was pushpin art; everyone put their art on the wall with pushpins, no frames, no glass. Many featured graph paper. I liked James Rosenquist’s idea of an impersonal style. I’d usually make mistakes on my graph paper. I’d knock over a cup of coffee, then accidentally walk on the paper. These were not Frank Stella’s discreet coffee cup rings. I’d noticed New York subway signs. They looked like hard paper. I needed hard paper that could be cleaned and reworked. I wanted a unit that could go around corners on the wall, stack for shipping. If you made a painting and wanted it to be longer, you could add plates. If you didn’t like the middle you could remove it, clean it, replace it or not. There had to be space between the units to visually correct plate and measuring distortions. My dilemma was, which measurement system, feet and inches or metric? In 1968 it was predicted that we would go metric. I bet we would continue with our standard measuring system. The smallest large unit of that system is one foot. The plates were cold-rolled steel, one foot square with a baked enamel surface, and a small hole in each corner with which to fix the plate to the wall. A quarter-inch grid is then epoxied onto the baked enamel. I went on the bus to see Gersen Feiner at his factory in New Jersey. He made the plates with deburred edges and sub-contracted the enamel surfaces to someone who did home appliances. He continues to make them for me.

EM Your grid was a given. You worked out very inventive systems. Did you know Sol LeWitt then?

JB I thought Sol was wonderful. And I think he may have recommended the silk-screener Joe Wantanabe, who screened the first plates with the quarter-inch grid. You know that problem in high school when everyone’s wearing a certain kind of shoe—in my case it was Joyces or Teardrops—and you buy a version of that shoe, and it’s much more wrong than if you had been independent and worn mukluks. In New York, I felt a distance between myself and others. I didn’t understand a lot of what was going on, what people said or how people felt about art. I feel that to this day. I don’t feel threatened by it anymore. I don’t understand, sometimes, what other people are seeing, or what they’re after, but back then it seemed necessary to pretend that I understood. Sol LeWitt’s “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” had been published, one of the great mid-century poems. And on a good day I could follow 15 of his 32 rules. I first showed at Alan Saret’s. He was very supportive. He built a bamboo stairway, beautiful, and I fell through and went to the hospital to have my leg seen to. I saw a lot of Alan during that time. Very much his own person, and completely honest.

EM When did you first show the plates, at Alan’s?

JB In 1969, 1970. My first gallery show was at Reese Paley’s in January 1971. I was on crutches. After I fell through Alan’s staircase I continued injuring one leg or the other before each show, group or solo.

EM Where was that gallery?

JB On Prince; it’s where the Mercer Hotel is now. He showed European and American artists, including Barry LeVa with whom I went to high school in Long Beach. Reese Paley only wore black. Among the European conceptualists showing in New York City were Jan Dibbets, Hanne Darboven, Joseph Beuys with his wolf, lard, felt and copper. Reese had a show in which vats of blood bubbled. It was a German artist, or possibly Austrian.

EM I didn’t realize that they started with the blood that early.

JB The blood was early; also decomposed stuff. I don’t know if they used them for the same reason that Damien Hirst does; I would think the shark would be more expensive, to get a good one that’s intact. I think Hirst’s work is more related to a water-based taxidermy.

EM What really costs money is getting it in the air.

JB All the technology, the refrigeration units.

EM We’re talking big bucks.

JB Interesting problems. I had my hard paper, the sets and series, the counting pieces. When I came to hang the show, I didn’t know where a piece began and ended, if it was a set within a series, a piece by itself, or the whole series. I did two big series. One was abstract and one was figurative. I think that an abstract painting is actually more figurative than a figurative painting, because it frequently is closer to the thing it is depicting. If you paint a red square, you have a red square of a certain measurable dimension. If you paint a vase of flowers, the vase of flowers is not measurable, more abstract than the red square.

EM Some people might disagree with you.

JB They did.

EM They would say, This is the difference between the phenomenon of the red vase and a phenomenology of painting, numinous, that which is only thought. I would say, looking around in your studio now, that that is really where your thinking is. You have an extremely eccentric way of combining these ideas. You put them into a paper bag, shake them, and out pops your unique way of looking at it all. Jennifer, your Reese Paley show was a big success. People were intrigued. I remember how beautiful it looked; it was fabulous the way it filled the space. It was very colorful and joyous, but it was also on a grid, so it was serious. You’d covered the bases. You had your conceptual ideas, you had a system, but you also had something really beautiful.

JB Thank you. I wanted to tell you about the two pieces hanging next to each other. Intersection which was abstract, and House, which was figurative. This is where the house image came from. I thought, What is the most common image in the USA that everyone would recognize? I picked a red house with a white picket fence, three hills in the back, and a pond with two ducks in it. I thought one would be able to purchase this painting or a variation at any dime store.

EM The house image has stayed with you since 1970; you’ve used it in your entire 40 years of artmaking.

JB That, plus the grid. Joel Shapiro was making beautiful house pieces at the time as well. I subjected this house scene to various scenarios. What would happen

if one element of the landscape left the painting in sequence, until the plate was blank? Now I realize I should have done it both ways, starting and ending with a blank plate. Adding and subtracting. I zoomed in on the house, through the open door, looking through a window with the landscape behind it that you couldn’t see because the house was in front of it. What would happen if I rotated the house, the four quadrants of the image? What if? Some people would like the intersection piece, and hate the house piece. I was curious about that. I became increasingly interested in setting up a circumstance where each system I had used—the house, a different set of suppositions than the intersection piece—became a “what if” situation. In 1971, Richard Artschwager, whose work I admire, came to the studio and said, If I’d invented these plates I’d really try different sizes, and different-sized grids. I thought, I see what you mean. In 2004, I added 50-centimeter squares, 18-inch squares and 24-inch squares with different grids. I get interested in following rules I select; I have found the visual results are always surprising. I did a simple counting piece, six colors in a sequence that builds so that each color expands its domination, starting always on the upper left-hand corner and reading left to right, and then drop down a line. The piece is called Ellipse. This way of counting created ellipses. I don’t know why. I understand the visual phenomenon but would not understand the explanation. But chaos theory made absolutely perfect sense to me.

EM Why do you think that is? What intrigues you so much about these number systems?

JB I have other ways of thinking about what we do. Because of you, I became interested in using oil on canvas. I started combining plates and canvas; then paper, plates, canvas, and glass. I made three-dimensional pieces that stood in front of the paintings that obscured or commented on them. Seawall and Fence are examples.

EM That’s interesting to me, because, even talking about Seawall and Fence,

“paintings with objects” has a whole different sound to it than talking about paintings that are about a house, or about numbers that develop ellipses through a counting system. I see a similarity in a way. You reach into the bag and you say, monsters, no babies. Or, babies standing up, babies lying down. Monsters in the corner. There’s always a system, whether it’s a dot or whether it’s monsters made up of dots. Am I right?

JB Yes. This painting started two years ago. There were nuns, and it was hilarious to me. These nuns sitting at a table and embroidering a theater curtain in Brussels. The nuns disappeared and became two trees, two windows, a table, two plates of fried eggs, and two chairs.

EM First of all, the painting is made up of one rectangular shape, and then two squares on top of it. So it looks like kind of an upside-down table shape.

JB I’d never thought of that.

EM The two trees make me think of something between Vuillard and Seurat—a Pointillist kind of thing. Like a little theater. I think there’s a theater aspect to your paintings that nobody ever discusses. A stage, and then you enact a play. Even in the most abstract ones, there’s some kind of a story going on. In this one, I see the two trees on either side so it’s kind of symmetrical. But then it becomes Matisse-y and Bonnard-like, with the red table and the two chairs. I like the painting; it’s really an intriguing painting. So far we’ve talked about the beginning of your real work, which starts in the very early ’70s, late ’60s, and was influenced by the kind of ideology and philosophies of what kind of art you could make during that period of time. What was permissible, and how you worked your way in and out of it. You fit in, and yet you had your own way of fitting in. So that you didn’t fit in. You always had an interest in the past. Van Gogh was the first guy that you fell in love with, because he’s all about those tiny, dotty marks, and building up an image with increments of paint that you can clearly make out. Seurat is about those little tiny dots.

JB On the way east, the train stopped in Chicago. I saw Seurat paintings for the first time, heaven. They were the right size. When I’d seen Gorkys, I was very disappointed: the size seemed wrong. I had thought they were bigger.

EM We saw those beautiful slides that knocked you over, then you saw the painting, “Hey, it’s a little squinty thing.”

JB The late ’60s and the ’70s was a time of incredible passion, and poverty. No one I knew was making their rent from art. I got into a cab, and the painter Bob Moskowitz was driving it. To sell a painting was an extraordinary event.

EM That’s so different now. Whether it’s good or bad, I don’t know, but I know that none of us had any money. Or expected to have any money.

JB Nope.

EM Everybody had day jobs, and you did art for the hell of it. Everybody was ambitious, and wanted their work to be seen. It had nothing to do with making money.

JB Do you remember all those art-for-fur-coats in the ’60s?

EM That happened to us, with Sidney Lewis.

JB When we got our washing machines! God bless Sidney Lewis.

EM Everybody’s first TV and first washer. The thrill when that happened, being able to order anything out of that catalog, like a slide projector, a washer-dryer. It was fabulous. Sidney Lewis brought the middle class to poor artists. I remember seeing all those shiny new appliances sitting around in everybody’s crummy apartments. There were no elevators; you had to carry all that stuff up these steep staircases.

Let’s get back to the monsters and work in the past. I stopped you because I was talking about Seurat and Van Gogh and how I see all of that stuff colliding in your work. I felt that we had a connection, although I saw you as further ahead than me. You had figured out a way to paint and not paint. You had that beautiful surface of the enamel plates.

JB If you did the same thing to a figurative image as you would to an abstract one, why would one look cozy and cute, and the other minimal and pure? I thought about the dialogue between Intersection and House.

EM They were almost like a film; you could edit and add and mix.

JB Except the plates were hard, and you could hold them, and see them. They were fixed to the wall, not illuminating it.

EM Then you did a show at Paula Cooper’s.

JB That was an all-black show, abstract systems. The house piece had lost. I rented a room in Provincetown from Jack and Wally Tworkov. Jack was working on paintings of chess moves. He said something that was important to me, about ambition. He said, “Can you imagine a situation in which you don’t have the kind of ambition you have?” I said, “What do you mean?” He said that the happiest moments in his life were not the big events, the attention. For him, a true sense of happiness might occur in the morning; pouring a bowl of cereal, he might look out the window and see that a bird had landed on the butterfly bush. I responded to this. I believe what Jack described has brought me joy all of my life, a grouping of things in stillness.

EM And this is something you feel you’d like to have in your paintings.

JB Yes. Then I think, the bird has blood, the bird can move like me. The bird can fly. The bird needs to eat to stay alive. The bush can move, it won’t move far, it will move in relationship to the weather, it will also move with the seasons in time. Then I’ll think, they’re both made of molecules, like me.

EM Why does that interest you? Something about mutability? What is it that fascinates you? There’s a key in there for what your work is about. What your life is about.

JB It makes me sad when I think about it. The bird’s going to die. The tree will too, but not quite as soon, unless something happens to it—acts of nature or man. It

is about mutability, in which things are changing from one state to another. The movies that, to me, were the most passionate are those of David Lean and Stanley Kubrick. I could never understand why people found them cold. I find them highly emotional.

EM They’re very mental, too.

JB They’re also physical.

EM I want to move on to Rhapsody.

JB Well, this is far after Rhapsody. I was standing in this ugly little garden in the south of France. It was like I was completely still, and everything was humming and in motion around me, but humming on different frequencies. The air was humming, the light was humming, that interested me.

EM And did you feel happy?

JB If happy can be defined as a kind of still bewilderment, with awe, yes, but alone, totally alone.

EM Would you say the culmination of part of your work was when you began to develop the ideas for Rhapsody? How did Rhapsody come about?

JB Rhapsody came out of the dialogue between Intersection and House. I began thinking about pieces not having edges: how do you know when a painting ends? I thought, what if it doesn’t end? What if a painting is like a conversation between the elements in the painting? I was thinking of a painting that wouldn’t have edges, that would start and stop, change tenses and gears at will. It needed to be big and fill the space in which it was shown. I asked, What can you have in art? I decided you could have lines: short, medium, long. They could be different widths: thin, medium, thick. They could be colored or not, horizontal, vertical, diagonal or curved, and any combination of the above.

EM So were you thinking at the time it would be like a dictionary or an encyclopedia of all the possible things you could make a painting of, or you could have in art?

JB Yes. I went on: you can have shapes; you can have colors. You can have figurative images. I selected four images. They were house, tree, ocean, mountain. Each category—color, line, shape, house, tree, ocean, mountain—had a section in which it would interact with the others.

EM You’ve always been interested in telling a story with your work. In the early pieces the story evolved from the puzzles or problems you set for yourself.

JB Yes. That’s everywhere in my work. The question I was never able to understand was the fight between abstract and figurative art. It made no sense to me. An abstract piece of work, like some of Mondrian’s, evoke in me so many sensations, primarily joy. I remember going to his show at the MoMA—it was like swimming; I swam through it. That’s a story to me. My requirements for a story can be brief: “I’m going to count, and I’m going to have one color expand and dominate the situation.” That’s a great story, to me.

It could be interesting to talk about this painting, the nun painting; you saw it from the beginning.

EM Oh, right. Describe the shapes, and then tell the story.

JB It’s a four-by-eight-foot rectangular canvas, hung horizontally. Two canvases, each 32 by 32 inches, are placed at the top right and left corners. Originally the two small canvases were on the lower corners of the painting; they were gardens at night. The large canvas showed a theater curtain that was used in another monster picture, which was a performance of an opera that doesn’t exist, based on Tess of the D’Urbervilles. Then there was another painting of a monster sitting and looking at an art book, in a quiet room. In the art book is a picture of the painting of the nuns, but I decided not to show the nuns. I changed the configuration of the canvases. Slowly, everything began going out of the painting. All that remained was a truncated version of the table at which the nuns had been working to embroider the curtains. Two chairs and two trees went in. The gardens became two windows. There are now two glasses of orange juice and two plates of fried eggs on the table. No one is at the table and the chairs are not facing one another. I put a bird in.

EM I see the bird. It’s sort of like what Philip Guston says about painting: “And finally even you leave the room.” Who were the nuns? I do remember the painting, and I was curious about why the nuns were in the painting in the first place.

Now this is a very cheerful, sunny painting. It looks like a breakfast nook. It’s

just bouncing with light and fun. The dots have this wonderful, sparkly, glimmery feeling.

JB Good.

EM But the nuns are gone. Who were they, and what are the monsters?

JB I’m going to have to answer this my own way, the way my mind works.

EM Well, Jennifer, I would not expect anything else.

JB Four years ago, I finished the Elements paintings. They had taken me eight years or so. I didn’t want to deal with any more imagery. I’d been through a

time of finding out information about my life that I had never known before. The information altered my perception of myself. I didn’t know what to think. It felt like a person had left the room, and I was left alone. I didn’t know the person who left. I didn’t know who I was. I didn’t want to do anything hard. I went back to the house image. I ordered about 30 canvases, different sizes, all squares, or double-square rectangles. I was looking ahead to my sixtieth birthday, and thinking about it two or three times a day, and what it meant. I thought, I can do anything I want, no matter how ridiculous. I started painting every possible way, every way I thought I might like to try. I was painting a picture, Houses in Motion. I had always wanted to do a cartoon painting. I looked at comic books to see what motion marks they had. There were houses blasting off, houses drilling into the earth, houses floating and flying, houses cracking in half. I was having a great time. I was working on a dotted picture, like the plates. I thought it would be funny if, in the middle of all these houses going off, two monsters saw each other. They’re much bigger than any of the houses. They haven’t seen each other in a long time; they were filled with longing. They lumbered toward each other.

EM These are the first monsters?

JB Yes. It was in a show of houses. They were the only monsters in the show.

EM That was a very autobiographical show, with paintings referring to events that happened when you were a kid. It was not a popular or a well-understood show. I can’t say I totally understood it myself, except it was autobiographical. I felt one of the problems with that work was how the figures in the Earth paintings were handled. They were all lumpy, and drawn in a cartoony children’s-book way. And they were doing all sorts of sinister things, but because they were lumpy they seemed harmless.

JB I really want you to see those paintings again; I think they’re some of the best paintings I’ve done. But you’re absolutely right. I tried to be specific to things I remembered. They were like cartoons taken from real life. I struggled to visualize these memories, and it does make the figures awkward. I think the houses are one form of the human presence in my work. I did a series of paintings, Swimmers, where I tried to make a more frontal account of human presence: I think it’s

like your image of the coffee cup, which represents human participation in an environment. I had ellipses as swimmers. They were black, brown, tan, pink; they all referred to human flesh tones. I thought I would try more ellipses in different sizes to convey the way we exist as bodies in the world. But that didn’t work. Now I am doing figures that have no real characteristics at all: the monsters.

EM What is a monster, to you?

JB The monster is not Philip Guston’s hooded figures. I love those paintings. I think there’s an element of wild despair and hilarity in his figures. My monsters, too, are a bit like us, but frequently my information is limited about them. They have nothing to do with memory now; they inhabit situations I imagine. That was why I had trouble with the nuns: I’m not a Catholic. The idea was like a joke that didn’t translate into paint for me. Someone in my studio looking at the Tess painting asked where the theater curtains came from. I’d made them up, so I said they come from nuns in Belgium who embroider curtains for all the major theaters here and abroad. It never worked out, as a painting.

EM You’re talking about the way the painting used to be. Did this come from a photograph? You don’t use photographs anymore, do you?

JB No.

EM So this was just sheer invention?

JB Yes.

EM I think it’s so interesting. Some of the paintings are determinedly abstract, and they’re about wonderful color arrangements; the color is very strong and very bright. They feel like fun, like this painting here, the zigzag painting over there. That’s just hilarious; an incredible use of line, the way the striated forms zoom back and forth and in and out. Then there are these paintings that are just about space and line and color and shape. And then there are these other funny, lumpy paintings of the monsters. They still use shapes and dots, but there are these Frankenstein-like figures floating in there that feel like they take form. They also feel like they want to be obliterated.

JB Yes.

EM They’re not doing anything, really, they’re just lumbering inside a space, like a thought in your mind that has no purpose whatsoever but you can’t quite obliterate.

JB Let me use, as an example, an abstract painting that intended to be a monster painting. The bottom canvas was a pool, and the top canvas was the figure of a monster looking into the pool and seeing its reflection. There were to be mountain peaks in the background, a Narcissus-like situation, a moment of quiet and peace. But it didn’t work out. I began to paint connections between angles I could find within the two canvases. The bottom was blue, and the top was red and green. Didn’t interest me. The image didn’t interest me, even though the image looked great to me, in terms of the shapes and sizes of the canvases. What I became interested in was how many angles were possible within the two canvases. The problem was how to paint the different angles so they could all be seen. I made them all different colors, but that didn’t look good. I put in another layer of color, over the previous colors, their complementaries. That didn’t look good. I put in a layer of beautiful gray over the colors. Everyone liked that, but I didn’t. I started using different-sized brushes for different-sized spaces. I put a coat of black on it but that seemed too chichi. I ended up doing an open coat of white, showing the colors, and a very open coat of black. That still wasn’t it. Now I’m in the process of doing the briefest coat of a color over each one that was originally there. Now that painting, which is about the same size, has one of the stiffest, clunkiest monsters. It was an elaborate painting, to begin with. It is also in transition. When I first saw these canvases up, they reminded me of a three-way mirror. I painted a grid. I’m obscuring the grid. It was a way to line up and make this room, this monster, these reflections, comprehensible.

EM I think that’s an amazing picture. We’re looking at it from an angle, but even when you’re up close to it, it has this weird perspective thing, where the middle is moving toward you and the right side squinches away. It’s almost mechanical; you really feel the perspective. That’s something about your work that I’ve always found fascinating, the wacky decisions about what the painting is going to be about, whether it’s putting in some mathematical equation that you want to elucidate, or if it’s a way of using ellipses and swimmers. There’s always the concept, which mechanically can make sense, then there’s the wacky philosophical or idea part of it that very often is completely whimsical and fantastical. Yet there it is, embodied in a physical way, with such determination and tenacity. And very great beauty. I think some of these paintings are so beautiful.

JB Really?

EM The one down there with the double arch over it, the swirl. What is in there?

JB It’s an honorary monster ball. (laughter) It’s very romantic; there are huge swags of silk hanging. The monsters are dancing and having a good time. Some of them are acrobatic; they appear and disappear in the curtains. This banner contains the writing that tells you what the event is. I don’t speak that language, I have absolutely no idea what it says.

EM So this rectangular shape is the theater, and this is—

JB The banner that makes it festive.

EM Here, next to it, is a kind of pyramid with the top shaved off. It’s like a manic carnival. The swirling discs put me in the mind of Duchamp’s discs, except they’re so much more fun. Then there’s a grid that kind of holds it all in place, but it’s completely nutty.

JB One thing that I like is the base color of the painting.

EM What is it called?

JB Grey of Grey.

EM Is it Holbein?

JB Yes. There’s just something about that that says everything to me, transparent and fugitive.

EM Part of the motivation of this painting, or its purpose, is to be able to use Grey of Grey as background.

JB Yes (laughter). As a background it doesn’t have to carry any weight.

EM So this is really an eye-dazzler.

JB Yes, I want them to be dancing in their imperfections, where I drip, or I go outside the lines, God forbid. This grid was drawn a long time ago—it’s really gotten off. I don’t feel like straightening it up.

EM It’s this fascinating combination of the conceptual, the painterly and the completely fantastical. How about this painting over here?

JB That’s going to be called Addenda.

EM These look like balloons, or big, five-day lollipops that have been cracked into and put on a shelf.

JB The small canvases show what the dots would look like in different sizes and shapes. It’s basically additional or alternative information for the viewer. Addenda is about these dots, and a certain group of colors. If I wanted to make another painting using those same colors in a plaid or in stripes, or in ellipses, I would also show those alternatives.

EM What would you call that? An action of the hand? An idea of the mind? It’s more than an exercise. What about the difference of that feeling that you have when you’re doing these very conceptual paintings and then the paintings with the monsters that begin to appear?

JB There’s always a formal issue. With the ones around the corner, or this one here, I have a very clear numerical system. I wanted to see what that specific system looks like on that specific space. All I have to do is do what I thought of doing. These are different than the early plate paintings. The plates already had a complex surface: steel, the enamel, the grid. Canvas doesn’t look that way. You know those Cézanne paintings, where there’s hardly any paint on part of the canvas, and then there’s a half an inch sticking out on another part. He leaves alone what is okay and reworks what is not working.

EM I hear enormous enjoyment in your tone about these particular paintings. You used the words “logic” and “justification.” One of the things that you begin to understand is that everything makes its own logic. I think this is your premise, even though it may seem totally simplistic or totally wacky.

JB That’s why Paula always thought I was a nihilist, because as soon as I would start on a system, I would want to invent a way of breaking the system and make it go off in another way.

EM Well, you see what I’m trying to get at?

JB Yes. I thought I was agreeing with you.

EM I didn’t get to finish my thought. You were talking about something that was completely uninteresting to you when you started your work, which was the early-‘60s and late-’50s battle between the conceptual and the process artists with the figurative people and action painters, and those painters with abstract painters: abstraction versus figuration. At this point, you’ve got both things going on in your work, if you call the monsters figurative, which they are and aren’t, but they do clearly have legs and arms and a head.

JB And that clearly looks like a tree or a chair.

EM Well, they’re images.

JB That’s the only thing I could never figure out, what figurative meant. If a painting is white with a red square in the center—

EM That’s the image.

JB It’s a red square. That is a thing. That is just as figurative to me as a blooming peony. I’ve never been able to make the distinction in my mind.

EM What exactly people do mean by abstraction.

JB I don’t know what they mean. I don’t know what they’re talking about. Like all of us, I wanted to be the best artist in the world, and I wanted everybody else to think so, too. I’d ask, “Am I being smart? Am I being stupid?” I’m old enough that the justifications are meaningless. Some things move me and they have to stay that way, even if I don’t like looking at them, and other things have to change, because they are not interesting to me. I spent 30 years trying to convince people and myself that I was smart, that I was a good painter, that I was this or that. It’s not going to happen. The only person that it should happen for is me. This is what I was meant to do.