BY SUZANNE JACKSON

February 9, 2021

September 28, 2020

Dear Mary,

Today, on my good computer, I was able to see the exhibition of your gorgeous paintings at Mnuchin Gallery from last winter. Somehow, even though the terminology of abstraction and expressionism and minimalism gets put on our work, we choose to describe our paintings relative to our independent process and the subsequent result for each work. We each build our own visual and spoken language; we choose our own respective vocabulary, outside of the canon of assigned definitions.

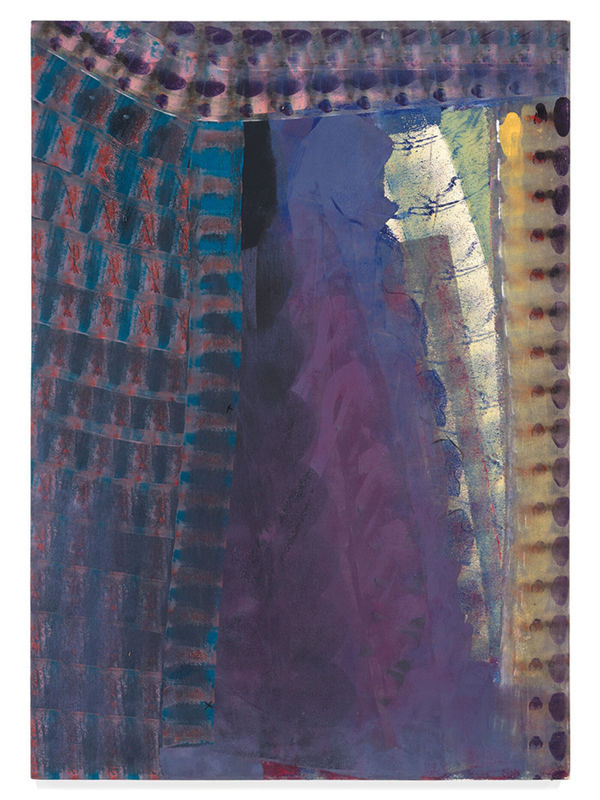

In the painting on the cover of your exhibition catalog Chasing Down the Image, I saw wolves and dogs and wild things. I had not realized that your series Panthers In My Father’s Palace originated during your time in Morocco. You were able to go places that I’ve always wanted to go and that I, too, have in my ancestry. I’ve been invited five times to travel to Africa; I even married a Nigerian, but I never made it to the continent. For me, the paintings from Panthers In My Father’s Palace say something about the totality of your vision on your trajectory from Mississippi to New York to the Bay Area. Remember the conversations we used to have? Those big arguments where all of us artists in the Bay Area and Los Angeles communicated with one another? I look forward to our virtual catch-up. We know that painting is the one thing both of us cannot stop doing.

Love and good health,

Suzanne

Mary Lovelace O’Neal: So, Suzanne, you’re in Savannah?

Suzanne Jackson: Yes, Georgia.

MLO: Melissa Messina is also based in Savannah. She included me in the Magnetic Fields exhibition organized by the Kemper Museum in Kansas City, which then traveled to two other museums.

SJ: Melissa was at Savannah College of Art and Design while I was still teaching there. I’m two years behind you in everything, Mary. I was born in ‘44 and you were ‘42. I think you retired from teaching at UC Berkeley in 2006. I retired in 2009.

Remember during the ceremony for your lifetime achievement award at the James A. Porter Colloquium in 2018, we sat next to each other and I introduced you to Melissa?

MLO: Yes, and we took pictures.

SJ: That’s right; we have a great photo where both of us are all wrapped up in furry clothes because it was so cold then. I’ve made a list of the times you and I have seen one another. We first met at the Santa Clara University in 1973. Diana Bates Edwards, you, and

I showed our work there.

MLO: That show at the museum with the French name? What’s it called again?

SJ: The de Saisset Museum in Santa Clara. The after party was at Marie Johnson Calloway’s house. And Arthur [Monroe] was running around trying to figure out where he was going to rest his head that evening and nobody would let him in. (laughter)

MLO: Violet Fields was there and she remembered Arthur’s antics in the pool that evening.

SJ: Arthur gave me a ride back to San Francisco and recited poetry and played Billie Holiday. EJ Montgomery had told me about him. She described him as an abstract painter living in a rough, unfinished warehouse in Fisherman’s Wharf. I’m always concerned about the serious artists who were in the Bay Area at the time—like Raymond Saunders, Oliver Jackson, Arthur Monroe, and you—because I think you are the most incredible painters and people have always treated all of us as if we didn’t exist. But we’re exhibiting all over the world.

MLO: Even within San Francisco, in the old days, they had real problems recognizing us. There was some recognition for African American men but rarely for the women artists.

SJ: I’ve always admired you for standing up to the guys. You argued them down like crazy.

MLO: We had to argue with them! These motherfuckers had to understand that we were painters.

SJ: That’s right, and they didn’t want us to be painters.

MLO: No, they wanted us to be the women who took care of them like their girlfriends did. Well, that was an absurdity.

SJ: You were such a character—rebellious, honest, and truthful. You weren’t putting up with anything. (laughter) And to defy all those guys as a student and to insist on taking a stand about the work you were doing was very important to me. People don’t realize that as Black women artists, we were really isolated, and we had to have the determination to do our work forever, no matter what.

MLO: You had to fight doubly to be seen; you had to fight those white boys that were making all the money and getting all the recognition, taking charge of all the theory, all of what could be argued about. And then you had these Black men who were also treating us like second- and third-class citizens—

SJ: Thank you!

MLO: So, you really had to fight for every inch, trying to out-drink them and out-curse them. You just had to be a bigger guy than they were.

SJ: That’s why you were so bold!

MLO: That’s real life.

SJ: We are both Aquarians.

MLO: You’re an Aquarius, too?

SJ: Yeah, my birthday’s January 30. That’s why we’re both crazy!

MLO: Mine is February 10. We’re right in the thick of it. (laughter)

SJ: You grew up in Mississippi—

MLO: I actually grew up in a lot of places. I remember best the years we spent at Pine Bluff, at Arkansas State University. Then we lived in Jackson, Mississippi. My father was chair of the music departments at Arkansas State, Jackson State, and Tougaloo College. My great-uncle was the president of Jackson State College. We would spend most of our summers and holidays in Chicago, or in Gary, Indiana, where my father’s family were from, after the migration. They had come up from Arkansas. Back then, most immigrants moved to those big steel towns, where people of color and foreigners were able to make a living and could have a home. We all knew each other; I remember the young white girls and boys that I played with in the alleys. Then when we went back to Pine Bluff, my world changed again, and I was only involved with Black people. I’ve got a story for everything.

SJ: You had the opportunity to study with fantastic people. Tell me about your time at Howard University and your studies with James A. Porter, Loïs Mailou Jones, David Driskell, and James Lesesne Wells, all influential twentieth-century artists.

MLO: Maybe we need to start with one of them.

SJ: How about James A. Porter? At the time, his Modern Negro Art from 1943 was the only art book to study.

I don’t think people know much about him aside from this book.

MLO: There are others who have, over the years, developed bigger profiles. Certainly Mr. Driskell. He had studied with Mr. Porter, Mrs. Jones, and Mr. Wells. There’s a lineage with all of us, including the late Mildred Thompson. Many people who came through the art department at Howard. I don’t want to get off on a long tangent, except to say that Mr. Porter and I had some difficult times. One of the things he was upset with was that I was spending so much time being involved in the student movement, both on campus and outside. He said, “Ms. Lovelace, being put in jail doesn’t add to your course credits.”

SJ: How was your experience with Loïs Mailou Jones?

MLO: She hated my work. She had other favorites. But I always sensed that all of our teachers were very proud of the stance many of us took in those days. Yet they were afraid for us, afraid that bad, bad things could happen to us in jail or that we would be killed. They all were concerned about coming up against Jim Crow. Washington, DC was still the South but it was also this great intellectual hub. The teachers were concerned that funding could be cut off. The government was even in control of how many lightbulbs Howard could have. How were we to sustain this great academic institution? Where would the money come from?

SJ: Can you talk about your involvement in the civil rights movement, especially while you dated Stokely Carmichael? Was that before or after Howard?

MLO: Carmichael and I were boyfriend and girlfriend at Howard. He went down to Mississippi and was part of a huge force of young students, Black and white, who came to support voter registration, labor issues, and those kinds of things. Howard students, along with others at historically Black colleges and universities like Tougaloo, Spelman, Morehouse, Fisk, and Tennessee State contributed richly to what became the student movement, the civil rights movement. Those young people joined the Freedom Riders—they were brave and often crazy.

SJ: Exactly, in defiance of parents and teachers.

MLO: And then you had Emmett Till, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner—and all those folks who became known for dying. I had to stay with the Schwerner family in New York because I did a big fundraiser for them in 1964. They invited me to spend the night in New Rochelle and they put me up in Mickey’s room. (sighs) And there were all the souvenirs that a young man would have—all the paraphernalia, all the bullshit you grow up with and that parents, suffering a great loss like that, keep. So there I was among all these precious things, and I just wanted to get out of there. Although I was a frontline person, I decided that I would no longer fundraise. I then went and helped find housing for people who had come up to Atlantic City, New Jersey—Black and white people who came north to confront the National Democratic Convention that year. All of those things played against the backdrop of my years at the art department at Howard. Carmichael actually joined one of my classes with Driskell and got a better grade on his paper than I did. I was furious.

SJ: I’d like to understand the transition in your early paintings—when you started working with this strong black pigment. Were those early lampblack paintings possibly connected to your moving from Howard to Mississippi to Africa?

MLO: Well, there were different times when I was in Africa. I was married to [Patricio Moreno] Toro and we went to North Africa together, to Morocco and Egypt. But let me locate the black work for you. John O’Neal, who was my first husband, and I were in New Orleans because of the Free Southern Theater that he and Gilbert Moses had started. They were working there taking theater to the rural parts of Louisiana and Mississippi, often places where people had never seen a play, except maybe a passion play. They had never watched television or seen a movie. So we traveled there with this troupe of Black people, white people, Asians, Chicanos, and Latinos.

SJ: There are so many parallels in our lives that connect us. I started college in San Francisco in ‘62. When I was nineteen, I auditioned to perform in a touring Free Southern Theater, and we were going to go south in a theater truck. But there was a controversy about whether the Blacks should travel in cars sitting in the front or the back or mixed up with the white actors. That came out in a San Francisco newspaper and my mother had a fit, so I wasn’t able to go.

MLO: Because John O’Neal was a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, we had to move 300 miles away. The theater had a fundraising arm in New York City and we decided to go there. And we stayed. It was my intention to never be in any school ever again. My life had been turned upside down and made miserable forever when I started kindergarten, and it never really got much better. I hated school all the years I was in it, all the years I taught. I’ve had the best time since retiring from the University of California. (laughter)

SJ: I agree. Retirement is wonderful as an artist.

MLO: In New York, I ended up at Columbia in the visual art graduate program. Along with being associated with the Black Arts Movement, I was again living that duality of social concerns and racial justice and trying to be a painter. The lampblack work was done at Columbia. My major professor there was Stephen Greene. His basic claim to fame was that Frank Stella had studied with him. He and I got into conflict from the beginning. As a Jewish man, he wasn’t prepared for all the social aspects of an African American student’s life that had to be dealt with. Aside from that, he was tired of de Kooning and didn’t appreciate the hot fast brushwork I was doing. He was trying to say, “This is no longer important; the guys with the minimal attitudes are the new sheriffs in town.”

Whatever they were teaching at Columbia could be found in real life just outside the door. This was New York in the late ’60s. There were all of these changes going on. All this wonderful stuff. I decided that I would just cool down my palette, so I started actually whiting things out, and then I worked almost exclusively with charcoal, pastels, and erasers.

While I was at Skowhegan in 1963, I’d seen this lampblack pigment that a visiting sculptor was using in a presentation. It was so beautiful and velvety; I fell in love with it. One day, at the Pearl Paint art supply store, I happened to see a whole pile of this black powder, and I bought five bags of it. At that point I was trying to figure out how to make my drawings into big works. John O’Neal was still building my stretcher bars, so I told him that I needed 7 by 11 or 12 feet, and he built them for me. That was one of the horrible things about being divorced from John—I had no one to build my stretcher bars.

SJ: (laughter)

MLO: My studio was this white space with vast expanses of white canvas. I would go in there and look at these packages of pigment, and finally I decided to go for it. I would take that black stuff and rub it into the canvas with a blackboard eraser and get the flattest painting ever. And it would also be the blackest painting.

John and I used to have all these Black artists and poets come to our apartment and smoke a million cigarettes and drink cheap brandy and argue. They were always on me about my work not being Black enough. They refused to deal with the whole question of abstraction that comes out of Africa, and I made the argument with them that this is exactly what I was making, what it was about for me. But my painting also answered the social question of Blackness, and it also answered the theoretical question about Black painting. I then started to move the work around in different ways—I was drawing under it, painting into it, and so on.

SJ: Did you use any color at that time?

MLO: I never left color as such. There was always something happening here and there on the edges. It might be just a blue dot in all of that black stuff which was my way of saying minimalism wasn’t enough.

I was very lucky to find this fantastic lampblack pigment and learn its limitations. I would gesso only parts of the canvas, so it would take paint in a certain way. People associated my works with Newman and Rothko. And quite possibly, I was being influenced by them because that’s what I had seen in the New York galleries.

SJ: Tell me how you came to printmaking.

MLO: Joe Overstreet and his wife, Corinne Jennings, had put a show together at Kenkeleba House in New York. I can’t remember who else was in it, but I was showing some big paintings, and Robert Blackburn came to the opening. As we were leaving, he said, “Mary Lovelace, do you want to come down to the print shop and make some prints?” And I said, “Bob, I really thank you for the invitation, but I don’t know anything about printmaking.” I had had such a horrendous experience with printing at Howard. I was always making a mess; I left a plate in a brand-new batch of acid and went off with friends to have dinner. I didn’t remember I had left it until the next day or even later. I ruined this whole new batch of acid. My teacher went off. (laughter)

I found the whole process of etching tedious and foolish; it was just not for me. But I didn’t say that to Bob. That evening after the show, we all went out barhopping and then we went to this wonderful street fair with all kinds of food and games. We were eating hot dogs and hamburgers and drinking beer with vodka or brandy. When I woke up the next morning my hair hurt. I mean, I just felt awful, and I said to myself, “I have to get up. I have to earn my breath today.” And I decided to go to Bob Blackburn’s studio. I fell in love with printmaking that day because he introduced me to monotypes—the closest thing to painting. And later I fell in love with lithography and etching, all of it! I was ready for it then. I thank Bob.

SJ: Sometimes it’s our early academic experience that can throw us off. But we also need it, so we can get freedom afterward, when we work on our own, and we’re our own boss.

MLO: I think I understand that too, now. I absolutely loved printing, even the cleanup after splashing all that lithotine around. Well, of course you’re high as the sky and you don’t even realize it. They say “as mad as a hatter,” and that’s because hat makers used all those strong chemicals. Many—Bob and a lot of other printmakers and painters, myself included—have been crippled by the chemicals we used. We knew the danger, but we were so busy chasing down the image that we just threw caution to the wind. Like, Fuck it. Let’s smoke cigarettes—

SJ: —in the midst of the paint and turpentine and all of that, yeah.

MLO: You know, I became a part of another wonderful print shop, Taller 99, in Santiago, Chile. It’s a communal workshop; people vote to let you come in and work with them. Nemesio Antúnez, who was the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art and, along with Roberto Matta, the organizer of that print shop, invited me. I’ve printed there ever since I went down there in 1989, right after Pinochet was taken out of office.

Eventually I had to erase all oil inks and paints out of my life because that stuff was literally killing me. So I ended up offering the first course in water-based printmaking at Berkeley. It’s difficult because after printing with oil-based inks, there’s nothing like it. But like many things, you have to not expect one thing to be the other thing. Why have two things if one is not going to be different? I learned to drill for what is unique and wonderful about each material. I taught a class of students who were accustomed to working in oil-based inks, and they were very upset. But by the end of the semester, we had found new solutions and new ways of working, like dampening the paper and using detergent to do some of the jobs that turpentine had done to break up the inks.

SJ: That’s pushing the limits. Every day there’s some other thing to learn, and we also make that problem, that experiment, to investigate. Challenge, that’s a better word for it.

MLO: Bob Blackburn later invited me to go to this big international festival that’s held in Asilah in Morocco. This was 1984, and it was there that the series Panthers In My Father’s Palace came about, because I actually lived in a palace. The printmakers were there for the entire month and there were theater groups and musicians. There was entertainment every night and huge conferences with poets and writers. It was an unbelievable experience.

SJ: You’ve traveled a lot in your life. Did the light in other places affect what’s happened in your painting?

MLO: Yeah. I moved to California; I was sort of a part of that westward migration of flower children. I mean, I wasn’t interested in their thing, but with the upheavals at Columbia, I decided, I don’t have to be in this, I’m not going to jail. Tear the school down, I don’t care. Coming to the Bay Area, I immediately noticed the light out here. There could be these huge black, black, black spaces of flatness in the sky and then there would be a shot of light breaking through there. If you saw something like that where I grew up, you got to safety because something big, bad, and ugly was about to come—a tornado or a hurricane, or a tremendous storm. But here in Northern California it was just light play; those black clouds would roll by on the way to somewhere else. I was taken by that light, and it became part of my paintings. They took on some softness against very hard areas. You don’t even know when something starts to change your work. After six or eight months I was like, Wow, how did that happen, and what is that about? The theory of flatness was no longer of central importance, and the whole space started to open up. Apart from the light, my encounters with the whales entered the work. Whatever is part of my life is what my painting is about. What I do is what I think about, or don’t want to think about sometimes. It’s about love; it’s about hate. All of those things somehow show up.

SJ: I want to talk about one of your paintings that I remember as one big brushstroke. The title was whalesfuckingwhales—all in lowercase as one word. I was so impressed with this title’s poetry; it was not immediately easy to read. Now it sounds like you have a whole series of those Whales Fucking paintings?

MLO: I do!

SJ: The series was so bold. I thought, Wow, this woman puts it right out there. And of course, I love the D.H. Lawrence poem, “Whales Weep Not!”: “They say the sea is cold, but the sea contains the hottest blood of all, and the wildest, the most urgent...” In my mind, that’s the way you paint.

MLO: And that was the way I felt about it. I had never seen a real whale before, but then, walking on a beach near San Francisco, I saw several white whales. That particular day, as God would have it, they were on their way north, and I got to see them following me as I walked on the beach. And watching them, I thought, Imagine the tons and tons of water they must displace when they’re fucking! So I started thinking more about that and also in terms of my own sexual experience. I won’t go deep into that, but that kind of rollicking...

SJ: It’s also that part of life that makes no excuses. Do you consider these perceptions transitions of the spiritual to material forms, or from material to spiritual?

MLO: There are those things like life and death. The loss of someone gets played out in my studio.

SJ: In the paintings from Panthers In My Father’s Palace, you seem to be pushing ancestry, migration, transcendence through color and shape. How do you build the structure and impact of color and line?

MLO: I’m moving space around. I’m trying to figure out how deep it is, sometimes how many chairs I can fit into this space, or how flat is this? I can’t count my change at the grocery store, but I know how to divide up a canvas, and I’ve got a good sense of what is mathematically possible and appropriate for my space. How much do I want you to come in and explore? How far do I want you to be able to go? I could be putting up barriers for you inside the painting. But I rarely do that because almost always I’m inviting you in.

SJ: I like that. The combination of brushstroke and shape seems very important. That’s what affected me so much when I first saw your whale paintings at Santa Clara. That one big brushstroke across the top could say everything. Is that a physical response, using your whole body in movement, or does it happen first in your mind?

MLO: Painting for me is aerobic. I’m up and down ladders, putting the paintings up on the wall and taking them down, putting them on the ground and moving around, getting in the center of them and pushing a line or a mark, or putting the canvas in tubs of water with dye and splashing around—and then quieting all of that. Because paintings will take over, and then you’ll have to get on it with them and say, “Hey, this is my fucking painting, give me that.” And they’ll say, “I can’t give you that.” And you keep working on it, trying to quiet it because there comes a point after you let the painting have its way, when you have to reign it back in.

SJ: Whoa, I love that.

MLO: Those paintings have a mind of their own.

SJ: Is that part of a spiritualism and mysticism, like we are combating spirits? Or our own demons?

MLO: No, we as Black folks—and I’m from the South—are deep into things having their own mind. Like this spoon has its own mind. And it’s true that all of these so-called inanimate things are animate. And it’s the same way with paint. Paint can lie. You know, it can say this is an apple, and it isn’t. Or it can say, “I’m being very, very quiet,” but then you pull a little zipper back and see all this activity in there. Like the whales fucking and moving all of that water around, rollicking and getting drunk. Let’s say you’ve finally gotten everything in order in your paintings, and you say goodnight to them, and you come back the next day and open the door and they are just getting back into their places. They have been boogying all night and drinking and now they are like, (whispers) “She’s back!” And you go, “Okay, I caught you. I got it. All of you go back.” And they’ll kind of squeeze back in, somewhat sullen and hungover.

SJ: (laughter) I just saw a photo from the installation at the Art Institute of Chicago. Your painting Running With My Black Panthers and White Doves (1989–90) can be seen through the corridor, and my painting is hanging in the next room. I am really happy to be in that exhibition with you.

MLO: And Sam Gilliam is in that same room.

SJ: Yes. I also had that privilege in the Brooklyn Museum show Soul of a Nation, Art in the Age of Black Power. I saw Sam’s painting and then didn’t even recognize my own work.

MLO: (laughter)

SJ: The way we were taught is that we weren’t supposed to get any recognition until a certain age. How do you feel about your work now versus back then? Do you find your earlier work better than you remembered?

MLO: When some of my paintings came out of their wrappers to go up in my show at Mnuchin this year, I hadn’t seen them in thirty years. And I thought, Wow, that girl can paint! Who is she? What is she to me? You know, it was simply incredible. I know now that I understood a lot of what I was doing, but everything was so fractured and so hard. Fighting for every brushstroke.

I understood my paintings, but I didn’t love them. And now I love them, I can truly see them. It’s like they are somebody else’s, but those are my paintings. They are strong. They are forceful. And they are saying something.

For Black women artists, it takes a while to love ourselves because we are so busy fighting. We wake up every morning with that fist, ready to fight another day, survive another day. Because life is difficult. I look at young people now—and it’s not a putdown—but everybody wants to be on the cover of Rolling Stone. You can’t be on the cover of Rolling Stone every month of your life. You’ve got to make the work.