BY ALEXIS OKEOWO

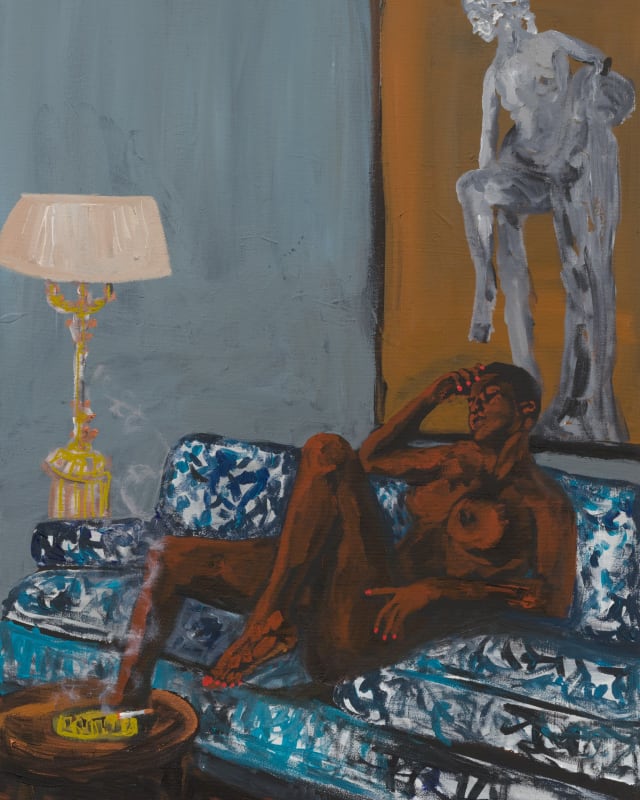

When I first saw the work of painter Danielle Mckinney, at a show at Night Gallery in Los Angeles last year, I got as close as I could without setting off the alarms. Her portraits of solitary Black women at home, beautiful and enigmatic, have a cinematic quality; Mckinney captures them with an acute female gaze—red lipstick, curls of cigarette smoke, pink nail polish—in moments of reflection, smoking, reading, or sprawled naked on a rug. “I wanted to paint this feeling of: When I get home and no one’s around, who am I? Who am I without this façade? And the interior space was perfect for that,” Mckinney says. In the Western art tradition, Black women tend to be at work, in the background, or at the edges of the frame—almost never centered and at rest. “You don’t get to see them lying down on a sofa,” she adds.

Based in Jersey City, Mckinney, who is 40, only started painting full-time during the COVID lockdown, but she had prominent space at Night Gallery, which co-represents her with the Marianne Boesky Gallery, where she will have a major solo show this October in New York. She has already had her paintings acquired by places like the Dallas Museum of Art, Miami’s Institute of Contemporary Art, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden at the Smithsonian; Beyoncé owns a piece too. “There is a strong sense of self that emanates from each solo figure, made all the more powerful by the intimate spaces that they not only inhabit, but command,” Thelma Golden, the director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, wrote me by email. “Her focus unveils assumptions around what is afforded Black women at rest, as much as it maintains a level of protective distance from the viewer. Ultimately, Danielle bringing these scenes to life is an act of reclamation.”

When I saw Mckinney’s paintings for the second time, this past February, it was at her studio, where canvases in various stages of completion lined the walls. They were moody, rendered in shades of shadowy brown, orange, blue, and green, and dominated by a languorous female form. Mckinney often paints from scenes she sees in photos and film, and listens to soul music and old R&B while she’s working. She always starts with an all-black canvas, and then lifts her figures from the background, followed by their rooms. On a mauve-pink table was a bound collection of vintage issues of Better Homes & Gardens that Mckinney ordered from eBay, which she uses, along with other magazines from the 1960s and ’70s, as references for her “minimal but pop” domestic spaces. Their imagery reminds her of her grandmother’s friends’ living rooms, with their plastic-covered printed sofas. Above the table, Mckinney had posted a sepia-toned photo of her father, who passed away when she was one. “He keeps me straight when I’m standing there looking around like, ‘Is this okay?’ ” she says.

We talked again over the summer, when she was at her gallery in New York and I was in London, where Mckinney had just visited with her artist husband, Robert Roest, and one-year-old daughter, Charlotte, after finishing a residency in Spain. We share a connection: We both grew up in Montgomery, Alabama. Raised on the outskirts of the city by her mother Barbara, aunt Frances, and grandmother Margaret, she was an only child. Mckinney remembers playing under the magnolia trees with friends, going to family reunions “out in the country,” passing days with her grandfather in his cow field in Lowndes County, and sitting with her grandmother’s friends on the porch as they knitted and played gospel music. “I spent a lot of time with older people. It was a sensitive time for me, but a very beautiful time,” Mckinney says. “My grandmother would put me in a room and give me all these magazines, and I would cut these figures out and build houses in shoeboxes. I would stay in there for hours, and I mean hours, and I would just be in my own world. It was the most comfortable, soothing feeling.” She presented the houses to her family when she was done.

Mckinney was drawn to the act of creating worlds with her own hands. “I was just restless, but art was my safe place,” she recalls. Her grandmother took her to painting classes, and her mom bought her a Nikon camera when she was 15. Mckinney began photographing her friends in nature, and studied photography at the Atlanta College of the Arts before going to the Parsons School of Design in New York. The move north was not easy; she was depressed for a year and felt out of place. But eventually, “Parsons became my family,” she says. While there, she pursued a project about intimacy, photographing people on the subway as she watched them in their “inner moments” and making a video about how strangers reacted when she touched them. After graduating, Mckinney stayed on working in the education department at Parsons and taking pictures in her free time. She submitted to photography open calls, but never heard anything back. Before the pandemic started, she felt stuck.

But she had been painting for years, and as an intern at the Studio Museum in Harlem in the summer of 2013, she discovered the portraits of Barkley Hendricks. (Mckinney is also captivated by the work of Jacob Lawrence, Francisco de Zurbarán, and Henri Matisse.) “Painting was like a diary for me. I would be in a relationship with a guy and have these feelings, and I would paint them,” Mckinney says of her early canvases. “And I started going at it really hard when COVID hit, because I couldn’t get out and photograph on the streets. So that was my release.” She set up easels in her spare bedroom, and after taking a virtual critique class, started sharing her paintings on Instagram. She wrote to dozens of galleries, including Night Gallery, which offered to give her a show the following year, in the spring of 2021. “I just sobbed,” Mckinney says. “I wanted to represent for all the times that I would go to openings at galleries and not see Black art.” After curators from New York’s Fortnight Institute saw her work, they also proposed a solo show, in April 2021—Mckinney’s first. Pregnant at the time, she was overwhelmed by the response at the opening, where a crowd of people waited outside. A few months later, Beyoncé and Jay-Z purchased her painting of a luminous woman in a billowing orange blouse, dangling a cross necklace above her head. “They support young Black artists, so I felt honored,” Mckinney says.

Her fall show will have paintings that feel more deliberative, inspired by changes in her life over the past few years. “Now it’s time to grow up,” she says. “I can’t go party and paint in the studio for 10 hours with a negroni and a cigarette. It’s about moving forward in my life, and the tension of that.” Dark green is a prominent color, and many of the women seem to be looking into an abyss. Her time in Spain moved her to start experimenting with leaving negative space around her figures, instead of painting them into rooms. But she remains “obsessed” with creating domestic worlds for her figures. “I’m kind of putting myself into those spaces,” Mckinney says. “I just hope I leave them open enough for people to feel comfortable coming in.”