BY JON RAYMOND

Widely known for her sculptures deploying old couches and cast-off furniture as host bodies for plaster obelisks, papier-mâché appendages, and homemade ceramic vessels, Jessica Jackson Hutchins for this occasion commandeered two Portland venues for a joint exhibition that amounted to something like a pocket retrospective of her work to date. “Confessions,” organized by Portland collector Sarah Miller Meigs and Cooley Gallery director Stephanie Snyder, offered Portland viewers a chance not only to commune with a hometown hero on an intimate scale but also to decipher how Hutchins’s crusty, blobular syntax has come into being. How is it that this work burns so cleanly through the fog of global art?

At Reed College’s Cooley Gallery, the works on view were largely recent, dating from 2012 onward. Exemplary among Hutchins’s numerous sculptures utilizing various seating elements, the wall-mounted Might, 2015, presented a grid of braille-like painted dots and some rough crosshatched lines on a swath of fabric attached to the backside of a hefty wooden stretcher. Smears of gray and mustard-colored paint were brushed across the verso of stretched canvas visible behind the fabric, and a sideways chair laden with a lumpy, dark-blue-green ceramic vessel was mounted to the frame’s bottom. Immediately in front of it was the freestanding Three Graces, 2013, a bulbous purple-, pink-, and acidic-yellow-glazed ceramic figurine resting on a sectional marred by matted paint (in shades of white and tapioca) and three teardrop-shaped burn marks. While the sculpture was ostensibly based on a photograph of colliding football players from a relatively recent New York Times Sports section clipping, the work’s classical underpinnings, intimated by its title, were reiterated by the urn form that rested atop the main ceramic mass, and by the peach-colored garland hanging below. Hutchins’s signature combinations of disparate materials and chronological references were unpredictable, even thrilling.

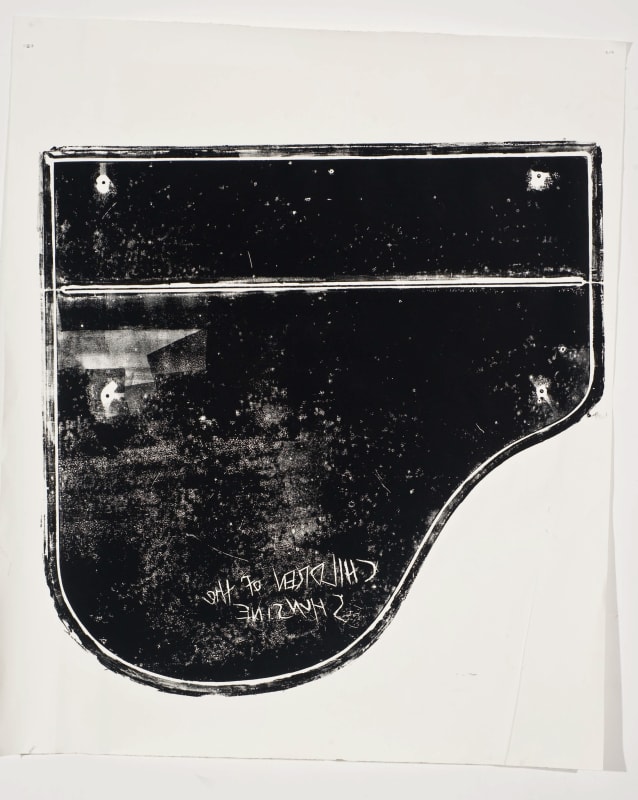

Across town, with a selection of works drawn entirely from Meigs’s private collection, the Lumber Room exhibition delved into the artist’s back catalogue. From 1999 came a series of collages, some made from Scotch tape and cut-up playing cards, arranged with a light touch suggesting a grunge Richard Tuttle; from 2006, two pieces stemming from a prolonged Darryl Strawberry obsession. Among the more recent works was Rope Stanza, 2013, a tarp painted eggplant and forest green with punches of yellow draped over a bent utility ladder, with a ceramic sack-form placed in the improvised tent’s “lap.” Strands of macramé suggested umbilical cords, and on the work’s side sat an algae-green pile of glazed ceramic, all of which gave the assemblage a witchy, salt-watery cast. The eggplant hue was a holdover from Untitled (Piano Print, M), 2010, a mostly black print made from the lid of a grand piano, decorated with wads of turquoise-, bister-, and lemon-colored clay and some scrawled lettering obscured by a scrap of sheer purple fabric—bandit bandanna, veil, or pubic triangle, depending on one’s frame of reference.

The double-chambered show evidenced a sensibility that has evolved in dramatic bursts over the years, both conceptually and literally. As Hutchins’s pieces have enlarged, her connection with the tangled roots of sculpture has also come to the fore. Her grammar seems particularly grounded in a holy trinity of postwar American artists: Johns, Rauschenberg, and Twombly. From Johns she has taken the half-scrutable erotic semiosis, the occasional exposed stretcher bars, the affixed “balls,” and the household objects; from Rauschenberg, a warmer, looser reliance on at-hand materials and the newspaper-based collage-as-rebus; and from Twombly, a certain mystical fogginess, the decidedly nongeometrical classical references, and a romantic employ of names from antiquity etched in rustic graffiti.

Hutchins’s shapes feel bracingly unauthored—a fungus of papier-mâché pimpled with decoupaged magazine clippings of wristwatches, a ceramic anemone with a wrinkled silk scarf. Rarely abject, her works are gropingly, spreadingly alive, rife with nuances by turns erotic, pious, funny, and gross. Out of the humble materials of plaster and old upholstery, she has birthed a vernacular, a brood of hodgepodge bodies who dream of olive trees and ancient light.